IDPro Body of Knowledgeの翻訳メモです。

元記事:https://bok.idpro.org/article/id/99/

IDPro Body of Knowledgeの翻訳メモのトップページ

Abstract

This article will provide an introduction to a widely deployed protocol named OAuth 2.0 (which stands for Open Authorization 2.0). It is used extensively with the large social media service providers as well as many other web-based services on the Internet today.

Keywords: oauth2, oidc, openid connect

Abstract

この記事では、OAuth 2.0(Open Authorization 2.0の略)と名付けられた広く普及しているプロトコルについて紹介します。このプロトコルは、大規模なソーシャルメディアサービスプロバイダーや今日のインターネット上の他の多くのWebベースのサービスで広く使われています。

Keywords: oauth2, oidc, openid connect

© 2023 IDPro, Bertrand Carlier

To comment on this article, please visit our _GitHub repository_ and _submit an issue_ .

About OAuth2

In a nutshell, this standard protocol aims to allow access from a client application (a website, a mobile application, an Internet-connected device, etc.) to a protected resource (e.g., an API), possibly on behalf of a resource owner (e.g., the end-user). It can be associated with several transport protocols but has been very popular to secure REST web services.

This article will focus on the current published standards; work is underway in the OAuth working group in the IETF to update some of this material. For more information on how OAuth came about and its relationship with other authentication protocols, see Pamela Dingle’s IDPro Body of Knowledge article, “Introduction to Identity - Part 2: Access Management.” 1

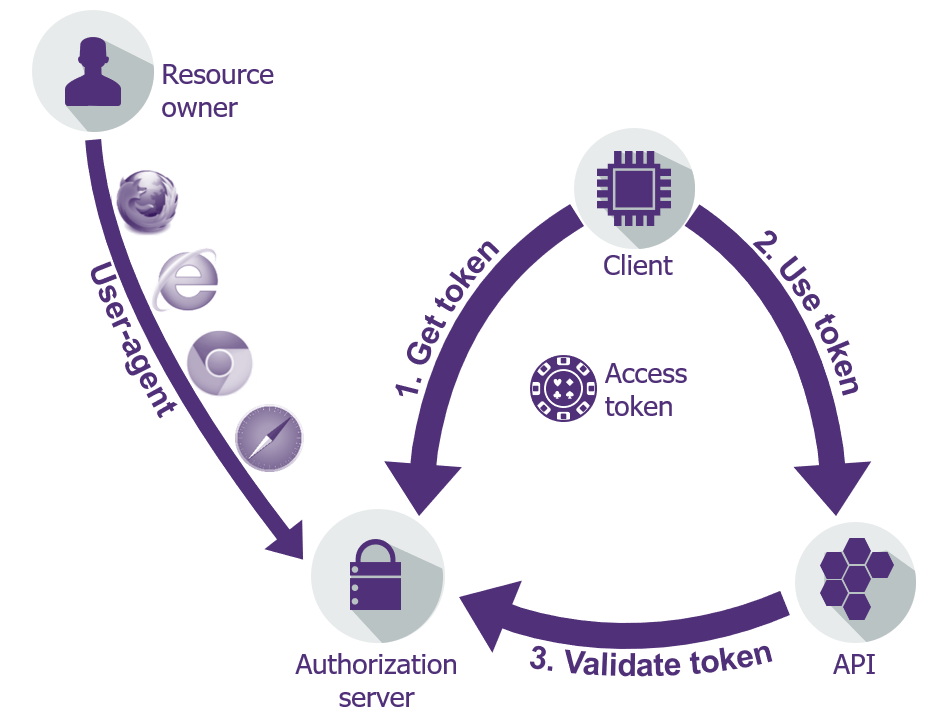

OAuth2 can be considered a three-step protocol:

-

Get an access token

-

Use the access token

-

Validate the access token

OAuth2について

一言で言えば、この標準プロトコルは、 クライアントアプリケーション (ウェブサイト、モバイルアプリケーション、インターネットに接続されたデバイスなど)から、おそらく リソース所有者 (エンドユーザーなど)に代わって、 保護されたリソース (APIなど)へのアクセスを許可することを目的としています。このプロトコルはいくつかのトランスポートプロトコルと関連付けることができますが、RESTウェブサービスをセキュアにするために非常に人気があります。

この記事では、現在公開されている標準仕様に焦点を当てます;IETFのOAuthワーキンググループでは、この資料の一部を更新する作業が進行中です。OAuthがどのようにして生まれたか、また他の認証プロトコルとの関係については、Pamela DingleのIDPro Body of Knowledgeの記事、「“Introduction to Identity - Part 2: Access Management」 1を参照してください。

OAuth2は3つのステップのプロトコルと考えることができます:

-

アクセストークンを取得する

-

アクセストークンを利用する

-

アクセストークンを検証する

Figure 1: High-level diagram of OAuth2 flows

Let’s see where to start the journey and where to head.

どこから旅を始め、どこに向かうべきかを見てみましょう。

Terminology

| Term | Definition |

| Client | A client application consuming an API |

| Protected Resource | An API in the OAuth2 terminology |

| Resource Owner | An end-user using the client application and granting it access to the protected resource |

| Authorization Server (AS) | The OAuth2 server is able to authorize a client, issue tokens, and potentially validate tokens |

| Scope | A string designating a (part) of a protected resource that a client is authorized to access |

| Bearer token | A token whose possession is sufficient to enable access to a protected resource |

| Sender constrained token | A token whose possession is not sufficient to enable access to a protected resource (additional proof of identity by the client application is required) |

| Access token | The OAuth2 token that allows a client to get access to a protected resource |

| Refresh token | The OAuth2 token that allows a client to renew an access token when it is expired without the user’s presence |

用語解説

| 用語 | 定義 |

| クライアント | APIを利用するクライアントアプリケーション |

| 保護されたリソース | OAuth2の用語でのAPI |

| リソースオーナー | クライアントアプリケーションを利用し、保護されたリソースにアクセスすることを許可されたエンドユーザー |

| 認可サーバー(AS) | OAuth2サーバーは、クライアントを認可し、トークンを発行し、場合によってトークンを検証することができます |

| スコープ | クライアントがアクセスすることを認可される保護されたリソース(の一部)を指定する文字列 |

| ベアラートークン | 保護されたリソースへアクセスするには所持していることで十分なトークン |

| 送信者制約付きトークン | 保護されたリソースへアクセスするには所持していることだけでは不十分なトークン(クライアントアプリケーションによる追加のアイデンティティの証明が必須) |

| アクセストークン | クライアントが保護されたリソースへアクセスすることを許可するOAuth2トークン |

| リフレッシュトークン | アクセストークンが有効期限切れとなったとき、ユーザーの存在なしにアクセストークンを更新することをクライアントに許可するOAuth2トークン |

Where to start

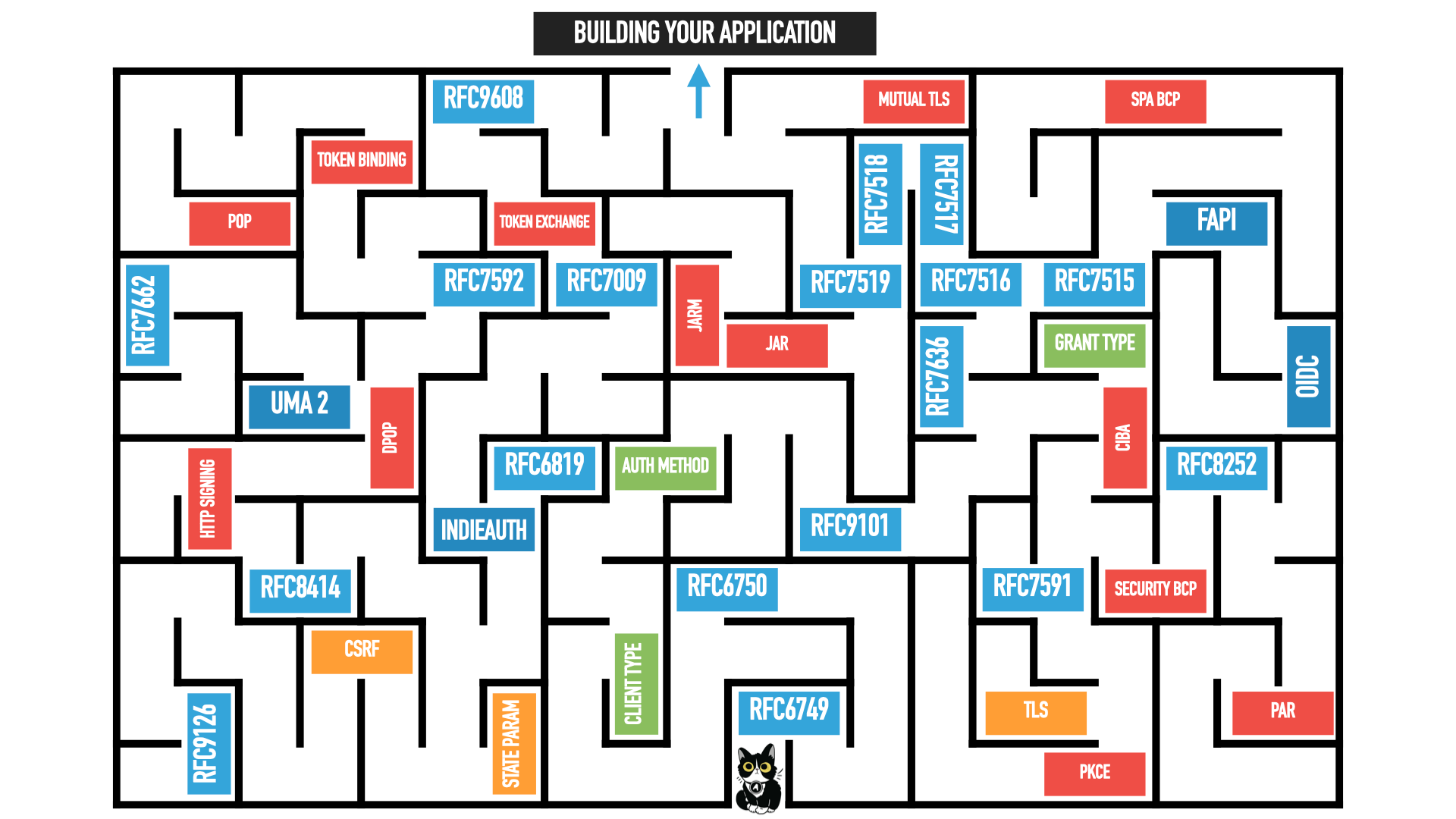

OAuth2 is defined through a series of IETF RFC documents that each describe a specific aspect, use case, or profile of use of the protocol.

どこから始めるか

OAuth2はIETF RFCの一連のドキュメントによって定義されており、それぞれがプロトコルの特定の側面、ユースケースまたは利用プロファイルを記述しています。

Figure 2: An artistic rendering of OAuth and related standards, courtesy of Aaron Parecki

-

RFC 6749 - The OAuth 2.0 Authorization Framework defines four ways for a client application to obtain a token from an authorization server (two of those are now deprecated). Those are called flows or authorization grants. 2

-

RFC 6750 - The OAuth 2.0 Authorization Framework: Bearer Token Usage defines the way for a client application to use a token in a subsequent request to a protected resource. 3

-

Later on, different documents would help with the validation step:

-

RFC 7662 - OAuth 2.0 Token Introspection defining token introspection against the authorization server, which can be used to verify token validity and extract data from the token. 4

-

or RFC 9068 - JSON Web Token (JWT) Profile for OAuth 2.0 Access Tokens defining a JWT profile for the access token. 5

-

Let’s use this breakdown to see what OAuth2 offers.

-

RFC 6749 - The OAuth 2.0 Authorization Frameworkは、クライアントアプリケーションが認可サーバーからトークンを取得する4つの方法を定義しています(現在ではそのうち2つは非推奨です)。これらはフローもしくは認可グラントと呼ばれます。 2

-

RFC 6750 - The OAuth 2.0 Authorization Framework: Bearer Token Usageは、クライアントアプリケーションが保護されたリソースへの後続のリクエストでのトークンを利用する方法を定義しています。 3

-

その後、別のドキュメントでは検証手順に役立ちます:

-

RFC 7662 - OAuth 2.0 Token Introspectionは、トークンの有効性を検証したり、トークンからデータを取得したりするために利用できる認可サーバーに対するトークンイントロスペクションについて定義しています。 4

-

もしくは、RFC 9068 - JSON Web Token (JWT) Profile for OAuth 2.0 Access Tokensは、アクセストークンのためのJWTプロファイルを定義しています。 5

-

OAuth2が提供するものを確認するため、このブレークダウンを利用しましょう。

Get a Token:

This step can be seen as a two-step process: first, the client must be authorized for an access token, then the client will perform a token request.

-

As mentioned above, of the four initial ways to obtain a token, two are deprecated following OAuth2.1 (currently draft):

-

Resource Owner Password Credentials, which encouraged an anti-pattern of sharing end-user credentials with the client application

-

Implicit flow, which made extensive use of the browser’s front channel and therefore introduced security issues

-

-

The two recommended flows remaining are the following:

- Authorization code flow is the recommended way to obtain a token when a resource owner is present and needs to authenticate first and then consent to delegate access for the client application to the protected resource. This flow uses redirections within a user-agent, typically the user’s browser, as well as a back-channel request to eventually obtain the OAuth2 Access Token.

There is a first step to authorize the client to get an access token and then a second step where the client actually gets the token.

An additional protection to the original Authorization Code flow is now recommended in order to tighten the security of OAuth2 authorization and deliver the Access Token to the legitimate client that initiated the request. The name of this additional protection is PKCE (for Proof Key Code Exchange, pronounced “pixie,” as defined in RFC 7636 ) and is considered a good approach to handle public clients. 6

- Client credentials aim to authenticate the client application only to deliver the access token (in that case, the AT is not linked to an end user’s identity but only to the client application identity). This flow is suited for application-to-application access.

トークンを取得する

このステップは2ステッププロセスと見ることができます:まず、クライアントはアクセストークンのための認可されなければならず、そしてクライアントはトークンリクエストを実行します。

-

前述したように、トークンを取得するための4つの初期方法のうち、OAuth2.1(現在ドラフト)では2つが非推奨になります:

-

リソースオーナー・パスワード・クレデンシャルズは、エンドユーザーのクレデンシャルをクライアントアプリケーションと共有するアンチパターンを推奨していました

-

インプリシットフローは、ブラウザのフロントチャンネルを多く利用し、セキュリティ問題を発生させました

-

-

残りの2つの推奨フローは以下のとおりです:

- 認可コードフロー は、リソースオーナーが存在し、最初に認証をおこない、保護されたリソースへのアクセスをクライアントアプリケーションに委任することに同意する必要があるとき、トークンを取得するための推奨される方式です。このフローはユーザーエージェント、一般的にはユーザーのブラウザ、でのリダイレクトと、最終的にOAuth2のアクセストークンを取得するためにバックチャンネルリクエストを利用します。

クライアントがアクセストークンを取得することを認可する最初のステップがあり、クライアントが実際にトークンを取得する2つ目のステップがあります。

現在では、OAuth2認可のセキュリティを強化し、リクエストを開始した正当なクライアントにアクセストークンを渡すために、オリジナルの認可コードフローを更に保護することが推奨されています。この追加の保護はPKCE(Proof Key Code Exchangeの略、「pixie」と発音、RFC 7636にて定義)と呼ばれ、パブリッククライアントを制御する良いアプローチと考えられています。 6

- クライアント・クレデンシャルズ は、アクセストークンを渡すためだけにクライアントアプリケーションを認証することを目的にしています(この場合、アクセストークンはエンドユーザーのアイデンティティとは関連付けされず、クライアントアプリケーションのアイデンティティだけに関連付けられます)。このフローはアプリケーション間のアクセスに適しています。

Use the Token

This step aims to use the access token while calling the protected resource.

RFC 6750 describes how an access token should be conveyed to a protected resource. In a very brief summary, and in order of preference, the token should be passed as:

-

An HTTP header as a bearer token (Authorization: Bearer

) -

A POST parameter

-

A GET parameter (aka Query String parameter)

トークンを利用する

このステップでは、保護されたリソースを呼び出すときにアクセストークンを利用することを目的にしています。

RFC 6750は、どのようにアクセストークンを保護されたリソースに伝えるべきかを記述しています。非常に短く要約すると、優先順位の高い順に、トークンは以下のように渡されるべきです:

-

HTTPヘッダにベアラートークンとして(Authorization: Bearer <アクセストークン>)

-

POSTパラメータ

-

GETパラメータ(別名クエリ文字列パラメータ)

Validate the Token

Finally, the protected resource receiving a token needs to check the token’s validity. This token validation was, for a long time, left to implementations to define how to proceed:

-

The token format is not specified and can be anything from a randomly generated opaque string acting as a reference token to a quite frequently witnessed JWT signed value token ( RFC 7519 ), but it can be anything that would fit the designers of any given implementation. 7

-

If the token is opaque to the client as per the RFC, no specific instructions are defined regarding how the protected resource should validate it. It relies on an out-of-band and beyond-the-scope-of-the-specification process to agree between protected resource and authorization server on how to validate a token: digital signature validation and possibly decryption of a self-contained token (see RFC 9068 for standardization of this approach using JWT as the token format) or introspection of a reference token against an Authorization Server (AS) endpoint (see RFC 7662 for standardization of this approach).

It is generally recommended to rely on one of those two documents to help with interoperability between the protected resource and the authorization server

トークンを検証する

最終的に、トークンを受け取った保護されたリソースはトークンの正当性を確認する必要があります。このトークンの正当性は、長い間、どのように実行することを定義する実装に委ねられていました:

-

トークンの形式は指定されておらず、参照トークンとして振る舞うランダムに生成された不透明な文字列から非常に頻繁に見かけるJWT署名値トークン(RFC 7519)まで何でもあり得ますが、任意の実装の設計適するものであれば何でもよいのです。 7

-

RFCに従ってトークンがクライアントにとって不透明な場合、どのように保護されたリソースがトークンを検証すべきかに関する具体的な指示は定義されていません。トークンをどのように検証するかについて、保護されたリソースと認可サーバー間で合意するために、帯域外で仕様のスコープを超えたプロセスに依存します:デジタル署名検証および自己完結型トークン(トークン形式としてJWTを利用するこのアプローチの標準化をおこなっているRFC 9068参照)または認可サーバー(AS)エンドポイント(このアプローチの標準化をおこなっているRFC7662参照)に対する参照トークンのイントロスペクションなど。

一般的に、保護されたリソースと認可サーバーの間の相互運用性を助けるために、これら2つのドキュメントのうち1つに依存することが推奨されます。

Beyond the Basics

This section of the article now gives additional details on more aspects of the OAuth2 protocol and additional specification documents.

基本を超える

現在、本記事のこのセクションはOAuth2プロトコルのより多くの側面と追加の仕様ドキュメントについての追加の詳細情報を提供しています。

Scopes

OAuth2 does not allow a client application to access any resource without restriction once it has an access token. An authorization request and, ultimately, the issued token holds a scope (which is a list of space-delimited, case-sensitive strings) that will allow the protected resource to determine if the authorization was indeed given to access it.

スコープ

OAuth2は、クライアントアプリケーションがひとたびアクセストークンを取得したら無制限にリソースにアクセスできるわけではありません。認可リクエストおよび、最終的に発行されたトークンをスコープ(スペースで区切られた、ケースセンシティブな文字列のリスト)を持ち、本当にアクセスすることを認可されたかを保護されたリソースが判断することができます。

Get a Token (Also)

A few additional ways to obtain an access token were later provided through additional specifications:

-

SAML profile and JWT profile will allow the delivery of an access token in exchange for, respectively, a SAML token or a JWT token issued for a specific end-user or crafted by the client application itself in order to authenticate itself. 8

-

Device flow will allow Internet-connected devices to retrieve an access token even if they can’t display a browser or are input-constrained. 9 This flow will rely on the end-user using another device (e.g., a browser on a smartphone) to complete part of the sequence.

-

Token exchange will enable an access token to be issued in exchange of any other security token and will provide guidelines to correctly implement delegation or impersonation. 10

トークンを取得する(再び)

アクセストークンを取得するいくつかの追加の方法が、後に追加の仕様で提供されました:

-

SAMLプロファイルおよびJWTプロファイルはそれぞれ、特定のエンドユーザーに発行され、クライアントアプリケーション自身が自身を認証するために作成されたSAMLトークンまたはJWTトークンを引き換えに、アクセストークンを渡すことを可能にします。 8

-

デバイスフローは、インターネット接続されたデバイスがブラウザを表示できなかったり、入力に制限があったりしても、アクセストークンを取得できるようします。 9 このフローは、シーケンスの一部を完了させるためmに他のデバイス(例えば、スマートフォン上のブラウザ)を利用するエンドユーザーに依存します。

-

トークン交換は、他のセキュリティトークンと交換にアクセストークンを発行することを可能にし、委任または代行を正しく実装するためのガイドラインを提供します。 10

Tokens

Until now, only the access token was mentioned. It is the core token that OAuth2 provides to client applications. This token is generally a bearer token, meaning that any entity that gets access to it can use it to access the protected resource. This characteristic has several security implications:

-

The protected resource cannot be sure that the client application currently requesting access is the same one that initially obtained the token

-

The end user that may have had to be authenticated to allow the token to be generated may not be present anymore

Access tokens, therefore, can have different characteristics to mitigate those implications:

-

Time-limited tokens. The specification recommends that the access token has a limited lifetime.

-

Sender-constrained tokens. Recent specifications ( mTLS , DPoP , etc.) allow that access tokens can be bound to the initial client application using various mechanisms, generally involving proof-of-possession of a cryptographic key both at the token request and at the token usage and that the token is linked to that key material (through a public key thumbprint for instance). 11 As a consequence, a sender-constrained token can only be used by the application that requested the token. It is worth noting that while approaches like DPoP can protect against a stolen token, they do not protect against a stolen client ID/secret for a client_credential grant.

OAuth2 also defines the concept of a refresh token issued by the Authorization Server and shared with the client app. This refresh token will allow the client app to request a fresh AT (e.g., once it expires) and potentially a refreshed refresh token without having to involve the end-user, for instance. This can be used to maintain a decent UX in a single-page application (SPA) or to allow for offline access when the user is not present anymore, but the client app needs access to the protected resource.

トークン

ここまで、アクセストークンについてのみ言及してきました。アクセストークンはOAuth2がクライアントアプリケーションに提供する中核のトークンです。このトークンは、一般的にベアラートークン、つまりこのトークンにアクセスできるエンティティは保護されたリソースへのアクセスのためにそのトークンを利用できるということです。この特徴はいくつかのセキュリティ上の懸念があります:

-

保護されたリソースは、現在アクセスを要求しているクライアントアプリケーションが最初にトークンを取得したものと同じであることを確認できません

-

トークンを生成するために認証が必要だったエンドユーザーが既に存在しない可能性があります

そこで、アクセストークンはこれら懸念に対策するために異なる特徴を持たせることができます:

-

時間制限付きのトークン。仕様ではアクセストークンに限られた生存時間を持たせることが推奨されています。

-

送信者制限トークン。最近の仕様(mTLS 、 DPoPなど)は、いくつかのメカニズム、一般的にトークンリクエストとトークン利用の両方において暗号鍵による所有の証明をおこない、トークンを鍵マテリアル(例えば、公開鍵の指紋)に関連付けることによってアクセストークンを最初のクライアントアプリケーションにバインドします。 11 結果として、送信者制限トークンはトークンを要求したアプリケーションだけが利用できます。DPoPのようなアプローチでは盗まれたトークンから保護できますが、client_credentialグラントでのクライアントID/シークレットの盗難からは保護できません。

また、OAuth2は認可サーバーによって発行され、クライアントアプリに共有される リフレッシュトークン の概念を定義しています。このリフレッシュトークンは、クライアントアプリが、例えばエンドユーザーの関与なしに新しいアクセストークンをと更新されたリフレッシュトークンを要求する(有効期限が切れたとき等)ことを可能にします。シングルページアプリケーション(SPA)での適切なUXの維持やユーザーが存在しないがクライアントアプリが保護されたリソースへのアクセスする必要がある場合のオフラインアクセスをおこなうために利用されます。

Discovery

In order to help clients dynamically register against an authorization server or programmatically get information about the authorization server features and level of support, some discovery and dynamic registration specifications are also available:

Beyond OAuth2

Now that most OAuth2 specifications have been introduced, you can easily imagine how difficult it can sometimes be to navigate through them and ensure one’s implementation is solid and secure. OAuth2 working group members created additional documents to help:

-

RFC 6819 - OAuth 2.0 Threat Model and Security Considerations 14

-

OAuth 2.0 Security Best Current Practice (currently draft)

-

OAuth 2.1 (currently draft) is a minor but important revision to the standard that incorporates security best practices

-

RFC 8252 - OAuth 2.0 for Native Apps for best practices around native application clients on different platforms 15

-

OAuth 2.0 for Browser-Based Apps (currently draft) for best practices around Single Page Applications

OAuth2 is also a foundation upon which other protocols were developed, the most known among these being OpenID Connect.

-

OpenID Connect , as described in the specification, is a “simple identity layer on top of the OAuth 2.0 protocol.” 16 Contrary to OAuth2, which focuses on authorization delegation, OIDC focuses on authentication. It introduces another token ( ID Token ), which is shared between the Authorization Server (or OpenID provider) and the client (or Relying Party). This token is a JWT formatted token. It conveys information about the authenticated identity through standard-defined claims and information about the authentication itself (time of authentication, method used, etc.).

-

User-Managed Access 2.0 is another protocol defined on top of OAuth2 (as a new authorization grant). 17 It introduces additional tokens, but most importantly, it does introduce a new player in the picture: the requesting party, which can be different from the resource owner (in OAuth2, the resource owner is the requesting party).

OAuth2を超えて

ここまででOAuth2の仕様のほとんどを紹介しましたが、それらをナビゲートし、実装が強固でセキュアであることを確認することがどれほど難しいかは簡単に想像できるでしょう。OAuth2ワーキンググループのメンバーはそれを手助けするための追加のドキュメントを作成しています:

-

RFC 6819 - OAuth 2.0 Threat Model and Security Considerations 14

-

OAuth 2.1 (現在ドラフト)はマイナーですが、セキュリティ上のベストプラクティスを取り込んだ標準仕様の重要な改訂版です。

-

RFC 8252 - OAuth 2.0 for Native Apps for best practices around native application clients on different platforms 15

-

OAuth 2.0 for Browser-Based Apps (現在ドラフト) for best practices around Single Page Applications

また、OAuth2は他のプロトコルが開発される基盤となっており、その中で最も有名なものはOpenID Connectです。

-

OpenID Connectは仕様に記述されているとおり、「OAuth 2.0プロトコルの上の単純なアイデンティティレイヤー」です。 16 認可委譲に着目するOAuth2とは対照的に、OIDCは認証に着目しています。OIDCは別のトークン( IDトークン )を導入しており、これは認可サーバー(もしくはOpenIDプロバイダー)とクライアント(またはリライングパーティ)の間で共有します。このトークンはJWT形式です。このトークンは、標準化されたクレームによって認証されたアイデンティティについての情報と認証自体の情報(認証された時刻、利用されたメソッドなど)について伝達します。

-

User-Managed Access 2.0は、(新しい認可グラントとして)OAuth2上に定義された別のプロトコルです。 17 追加のトークンを導入し、最も重要なことは新たなプレイヤーを追加していることです: Requesting Party は、リソースオーナーとは異なる可能性があります(OAuth2において、リソースオーナーはRequesting Partyです)。

Additional Reading

For additional information on implementing OAuth2, these resources may be of assistance:

-

Richer, Justin, and Antonio Sanso. 2017. OAuth 2 in Action . Manning.

-

Parecki, Aaron. 2018. OAUTH 2.0 Simplified . Lulu.com.

追加の読み物

OAuth2を実装するための追加情報として、以下のリソースが助けになるでしょう:

-

Richer, Justin, and Antonio Sanso. 2017. OAuth 2 in Action . Manning.

-

Parecki, Aaron. 2018. OAUTH 2.0 Simplified . Lulu.com.

Author

Bertrand Carlier is a senior manager in the Cybersecurity & Digital Trust practice at Wavestone consultancy with 20 years of experience. He has been leading major Identity & Access Management projects, working with many client companies in a variety of industries.

He is devoted to promoting and encouraging the use of open standards and has done so through leading projects and talks at various international conferences.

He likes nothing more than to tackle the newest problems in the Identity and Access Management space: API & microservices security, IAM of Things, AI for IAM and IAM for AI, and, of course, the longstanding problem of “how to cope with both the legacy and the ever more shiny (and accumulating) new toys?”

-

Dingle, P., (2020) “Introduction to Identity - Part 2: Access Management”, IDPro Body of Knowledge 1(2). doi: https://doi.org/10.55621/idpro.45 ↩ ↩2

-

Hardt, D., Ed., “The OAuth 2.0 Authorization Framework”, RFC 6749, DOI 10.17487/RFC6749, October 2012, https://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc6749. ↩ ↩2

-

Jones, M. and D. Hardt, “The OAuth 2.0 Authorization Framework: Bearer Token Usage”, RFC 6750, DOI 10.17487/RFC6750, October 2012, https://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc6750. ↩ ↩2

-

Richer, J., Ed., “OAuth 2.0 Token Introspection”, RFC 7662, DOI 10.17487/RFC7662, October 2015, https://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc7662. ↩ ↩2

-

Bertocci, V., “JSON Web Token (JWT) Profile for OAuth 2.0 Access Tokens”, RFC 9068, DOI 10.17487/RFC9068, October 2021, https://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc9068. ↩ ↩2

-

Sakimura, N., Ed., Bradley, J., and N. Agarwal, “Proof Key for Code Exchange by OAuth Public Clients”, RFC 7636, DOI 10.17487/RFC7636, September 2015, https://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc7636. ↩ ↩2

-

Jones, M., Bradley, J., and N. Sakimura, “JSON Web Token (JWT)”, RFC 7519, DOI 10.17487/RFC7519, May 2015, https://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc7519. ↩ ↩2

-

Campbell, B., Mortimore, C., and M. Jones, “Security Assertion Markup Language (SAML) 2.0 Profile for OAuth 2.0 Client Authentication and Authorization Grants”, RFC 7522, DOI 10.17487/RFC7522, May 2015, https://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc7522 and Jones, M., Campbell, B., and C. Mortimore, “JSON Web Token (JWT) Profile for OAuth 2.0 Client Authentication and Authorization Grants”, RFC 7523, DOI 10.17487/RFC7523, May 2015, https://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc7523. ↩ ↩2

-

Denniss, W., Bradley, J., Jones, M., and H. Tschofenig, “OAuth 2.0 Device Authorization Grant”, RFC 8628, DOI 10.17487/RFC8628, August 2019, https://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc8628. ↩ ↩2

-

Jones, M., Nadalin, A., Campbell, B., Ed., Bradley, J., and C. Mortimore, “OAuth 2.0 Token Exchange”, RFC 8693, DOI 10.17487/RFC8693, January 2020, https://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc8693. ↩ ↩2

-

Campbell, B., Bradley, J., Sakimura, N., and T. Lodderstedt, “OAuth 2.0 Mutual-TLS Client Authentication and Certificate-Bound Access Tokens”, RFC 8705, DOI 10.17487/RFC8705, February 2020, https://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc8705 and Fett, D., Campbell, B., Bradley, J., Lodderstedt, T., Jones, M., and D. Waite, “OAuth 2.0 Demonstrating Proof of Possession (DPoP)”, RFC 9449, DOI 10.17487/RFC9449, September 2023, https://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc9449. ↩ ↩2

-

Richer, J., Ed., Jones, M., Bradley, J., Machulak, M., and P. Hunt, “OAuth 2.0 Dynamic Client Registration Protocol”, RFC 7591, DOI 10.17487/RFC7591, July 2015, https://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc7591. ↩ ↩2

-

Jones, M., Sakimura, N., and J. Bradley, “OAuth 2.0 Authorization Server Metadata”, RFC 8414, DOI 10.17487/RFC8414, June 2018, https://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc8414. ↩ ↩2

-

Lodderstedt, T., Ed., McGloin, M., and P. Hunt, “OAuth 2.0 Threat Model and Security Considerations”, RFC 6819, DOI 10.17487/RFC6819, January 2013, https://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc6819. ↩ ↩2

-

Denniss, W. and J. Bradley, “OAuth 2.0 for Native Apps”, BCP 212, RFC 8252, DOI 10.17487/RFC8252, October 2017, https://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc8252. ↩ ↩2

-

Sakimura, N., Bradley, J., Jones, M., de Medeiros, B., Mortimore, C. “OpenID Connect Core 1.0 incorporating errata set 1,” OpenID Foundation, November 2014, https://openid.net/specs/openid-connect-core-1_0.html . ↩ ↩2

-

Maler, E. (ed.), Machulak, M., Richer, J. “User-Managed Access (UMA) 2.0 Grant for OAuth 2.0 Authorization,” Kantara Initiative, January 2018, https://docs.kantarainitiative.org/uma/wg/rec-oauth-uma-grant-2.0.html . ↩ ↩2