IDPro Body of Knowledgeの翻訳メモです。

元記事:https://bok.idpro.org/article/id/94/

IDPro Body of Knowledgeの翻訳メモのトップページ

Abstract

Identity proofing, process by which a credential service provider collects, validates, and verifies information about a person, is a critical step for many identity systems. This article explores identity proofing in general and why current practices are challenging. While the article is largely informed by the identity proofing examples within the United States, the concepts are globally applicable.

Keywords: identity proofing, digital identity, Government, best practices, NIST SP 800-63-3

概要

身元確認、クレデンシャル・サービス・プロバイダーが個人に関する情報を収集、確認、検証する過程、は多くのアイデンティティ・システムにとって重要なステップです。本記事では一般的な身元確認と現在のプラクティスがなぜ困難なのかについて探ります。本記事では主にアメリカ国内の身元確認の例に基づきますが、そのコンセプトは全世界で適用することができます。

Keywords: 身元確認, デジタルアイデンティティ, 政府, ベストプラクティス, NIST SP 800-63-3

© 2023 IDPro, Russ Reopell, Sandy Christopher, and Lorrayne Auld

To comment on this article, please visit our GitHub repository and submit an issue.

Abstract

Identity proofing, process by which a credential service provider collects, validates, and verifies information about a person, is a critical step for many identity systems. This article explores identity proofing in general and why current practices are challenging. While the article is largely informed by the identity proofing examples within the United States, the concepts are globally applicable.

概要

身元確認、クレデンシャル・サービス・プロバイダーが個人に関する情報を収集、確認、検証する過程、は多くのアイデンティティ・システムにとって重要なステップです。本記事では一般的な身元確認と現在のプラクティスがなぜ困難なのかについて探ります。本記事では主にアメリカ国内の身元確認の例に基づきますが、そのコンセプトは全世界で適用することができます。

Introduction

Whether you’re purchasing merchandise online or requesting financial or medical services from the federal government or health care providers, being able to prove you are who you claim to be and are indeed entitled to the goods and services you are attempting to access has become a crucial and required fact of everyday life. This article helps readers understand the difficulties and challenges they may face in registering for online goods and services.

イントロダクション

オンラインで商品を購入する場合であれ、連邦政府や医療提供者から金融サービスや医療サービスを要求する場合であれ、自身が要求している自分であることおよびアクセスしようとしている商品やサービスに対して適切であることを証明できることは日常生活で非常に重要であり、求められるようになっています。本記事は、オンラインでの商品購入とサービスでの登録において直面する可能性のある困難や課題に対する読者の理解を助けるものです。

Terminology

Applicant : A subject undergoing the processes of enrollment and identity proofing.

Binding : Associating an authenticator with an identity.

Claimant : A subject whose identity is to be verified by using one or more authentication protocols.

Claimed Identity : An applicant’s declaration of unvalidated and unverified personal attributes.

Credential : An object or data structure that authoritatively binds an identity—via an identifier or identifiers—and (optionally) additional attributes to at least one authenticator possessed and controlled by a subscriber.

Credential Service Provider (CSP) : A trusted entity that issues or registers subscriber authenticators and issues electronic credentials to subscribers. A CSP may be an independent third party or may issue credentials for its own use.

Enrollment : Also known as Registration. Enrollment is concerned with the proofing and lifecycle aspects of the principal (or subject). The entity that performs enrollment has sometimes been known as a Registration Authority, but we (following NIST SP.800-63-3) will use the term Credential Service Provider.

Identity : An attribute or set of attributes that uniquely describes a subject within a given context.

Identity Evidence : Information or documentation the applicant provides to support the claimed identity. Identity evidence may be physical (e.g., a driver’s license) or digital (e.g., an assertion generated and issued by a CSP based on the applicant successfully authenticating to the CSP).

Identity Proofing : The process by which a CSP collects, validates, and verifies information about a person.

Identity Provider (IdP) : The party that manages the subscriber’s primary authentication credentials and issues assertions derived from those credentials. This is commonly the CSP as discussed within this article.

Knowledge-Based Authentication (KBA) : Identity-verification method based on knowledge of private information associated with the claimed identity. This is often referred to as knowledge-based verification (KBV) or knowledge-based proofing (KBP).

Registration : See Enrollment.

Remote : In the context of remote authentication or remote transaction , an information exchange between network-connected devices where the information cannot be reliably protected end to end by a single organization’s security controls.

Subscriber : A party enrolled in the CSP identity service.

用語解説

アプリカント : 登録および身元確認プロセスを実行中の主体。

バインディング : 認証器とアイデンティティの関連付け。

クレイマント : 1つ以上の認証プロトコルによってアイデンティティが検証される主体。

クレームドアイデンティティ : 真正性が確認されていない、未検証の個人の属性のアプリカントの宣言。

クレデンシャル : 識別子を介してアイデンティティおよび(オプションで)追加の属性をサブスクライバーによって所持および管理されている少なくとも1つの認証器に権威的にバインドするオブジェクトまたはデータ構造。

クレデンシャル・サービス・プロバイダー(CSP) : サブスクライバーの認証器を発行または登録し、サブスクライバーに電子的なクレデンシャルを発行する信頼できるエンティティ。CSPは独立したサードパーティである場合、その独自の利用のためにクレデンシャルを発行する場合があります。

エンロールメント : 登録としても知られます。エンロールメントは、プリンシパル(または主体)の証明とライフサイクルの側面に関係します。エンロールメントを実行するエンティティは登録局として知られることもありますが、ここでは(NIST SP.800-63-3に従って)クレデンシャル・サービス・プロバイダーという用語を使います。

アイデンティティ : 特定のコンテキスト内で主体を一意に記述する属性または属性のセット。

アイデンティティの証拠 : クレームドアイデンティティをサポートするためにアプリカントが提供する情報またはドキュメント。アイデンティティの証拠は物理的なもの(例、運転免許証)かもしれませんし、デジタルなもの(例、CSPで認証に成功したアプリカントをもとにCSPによって生成され、発行されたアサーション)かもしれません。

身元確認 : CSPが個人に関する情報を収集、真正性の確認および検証するプロセス。

アイデンティティプロバイダー(IdP) : サブスクライバーの一次認証クレデンシャルを管理し、これらのクレデンシャルに由来するアサーションを発行するパーティ。これは一般的にCSPとして、本記事内では議論されます。

知識ベース認証(KBA) : クレームドアイデンティティに関連しているプライベートな情報に関する知識に基づく身元確認の方法。しばしば、これは知識ベース検証(KBV)または知識ベース証明(KBP)と呼ばれます。

登録 : 「エンロールメント」を参照。

リモート : リモート認証またはリモートトランザクションのコンテキストで 、単一の組織のセキュリティ管理によって情報をエンドツーエンドで確実に保護できない、ネットワーク接続デバイス間の情報交換。

サブスクライバー : CSPアイデンティティサービスに登録されたパーティ。

Why do we need identity proofing?

Today, many companies and government agencies rely heavily on accurately identifying, credentialing, monitoring, and managing user access to information and information systems across their enterprise to ensure they know who is accessing their data. One of the challenges of digital identity is associating a set of online activities with a specific entity. There are numerous situations where it is important to reliably establish an association of a digital identity with a real-life subject. Examples include obtaining health care and executing financial transactions. There are also situations where the association is required for regulatory reasons (e.g., the financial industry’s Know Your Customer (KYC) requirements, established in the implementation of the USA PATRIOT Act of 2001) 1 or to establish accountability for high-risk actions (e.g., changing the release rate of water from a dam).

Identity proofing establishes that a person is who they say they are based on the validity of one or more pieces of identity evidence. The more due diligence incorporated into the identity-proofing process, the higher the confidence that the applicant is who they claim to be. For example, one would place little confidence in self-asserted identity (“I say I am Santa Claus, therefore I am Santa Claus”). However, suppose I claim to be Mother Nature and can provide written and corroborated identity evidence proving I am Mother Nature. In that case, there is a much higher level of confidence placed in that identity. If I provide all that documentation to the CSP in person, you can be sure I am who I claim to be.

身元確認がなぜ必要なのか?

今日、多くの企業と政府機関はデータへのアクセスをおこなっている人物を確実に把握するため、正確な識別、クレデンシャルの付与、監視および情報および企業の情報システムへのユーザのアクセス管理に大きく依存しています。デジタル・アイデンティティの課題のひとつは、特定のエンティティに一連のオンライン活動を関連付けることです。デジタル・アイデンティティと現実の対象を確実に関連付けることが重要なシチュエーションは多くあります。例えば、医療ケアを受けたり、金融取引をおこなったりする場合です。また、規制上の理由(例えば、USA PATRIOT Act of 2001に基づく金融業界のKnow Your Customer(KYC)要件) 1のために関連付けが必要になるシチュエーションや、リスクの高い行為(例えば、ダムからの放水速度の変更)に対する責任を明確にするシチュエーションがあります。

身元確認 は、1つまたは複数の身分証明書の正当性に基づいて申請者が本人であることを証明することです。身元確認プロセスにデュー・デリジェンスが組み込まれていればいるほど、申請者が本人であるという確証が高くなります。例えば、自己主張されたアイデンティティ(「私はサンタ・クロースと私が言ったので、私はサンタ・クロースです」)にはほとんど信頼をしないだろう。しかし、私がMother Natureであると主張し、私がMother Natureであることを証明する書面と裏付けされた身分証明書を提示することができたとします。この場合、アイデンティティはより信頼できます。もし私がCSPにすべての書面を提示できれば、私が主張する私自身であることを確信できます。

What is identity proofing?

Identity proofing is the process used by a credential service provider (CSP) to collect, validate, and verify the identity evidence provided by an applicant to establish a subscriber’s digital identity. The identity provider (IdP) manages the subscriber’s primary authenticators and, in federation agreements, issues assertions derived from the subscriber’s account. When an applicant is identity proofed, the expected outcomes are:

-

The claimed identity (a set of unvalidated and unverified personal attributes) is resolved to a single, unique identity within the context of the population of users the IdP/CSP serves and has been validated to exist in the real world.

-

All supplied identity evidence is validated to be correct and genuine (e.g., not counterfeit or misappropriated).

-

The CSP/IdP verifies that the claimed identity is associated with the real person who supplied the identity evidence.

When conducting an online transaction, a digital identity represents the person trying to access the digital service.

身元確認とは何か?

身元確認は申請者のデジタル・アイデンティティを確立することを目的に提示された身分証明書を収集、確認、検証するため クレデンシャル・サービス・プロバイダー(CSP) によって実行されるプロセスです。 アイデンティティ・プロバイダー(IdP) は申請者のプライマリ認証を管理しており、フェデレーション同意によって申請者のアカウントに由来するアサーションを発行します。申請者の身元確認をおこなうとき、期待される結果は以下の通りです:

-

主張されたアイデンティティ (一連の未確認、未検証の個人の属性)が、IdP/CPSサービスのユーザ集団内において単一で一意なアイデンティティとして解決され、実世界での存在が確認されること

-

提示されたすべての身分証明書が正確で真正であることを確認すること(例えば、偽造または盗難されたものではない)

-

CSP/IdPが主張されたアイデンティティが身分証明書が提示された現実の人物と関連付けられることを検証すること

オンライン取引を実行する場合、デジタル・アイデンティティはデジタル・サービスにアクセスしようとする個人を表します。

How is a Digital Identity created?

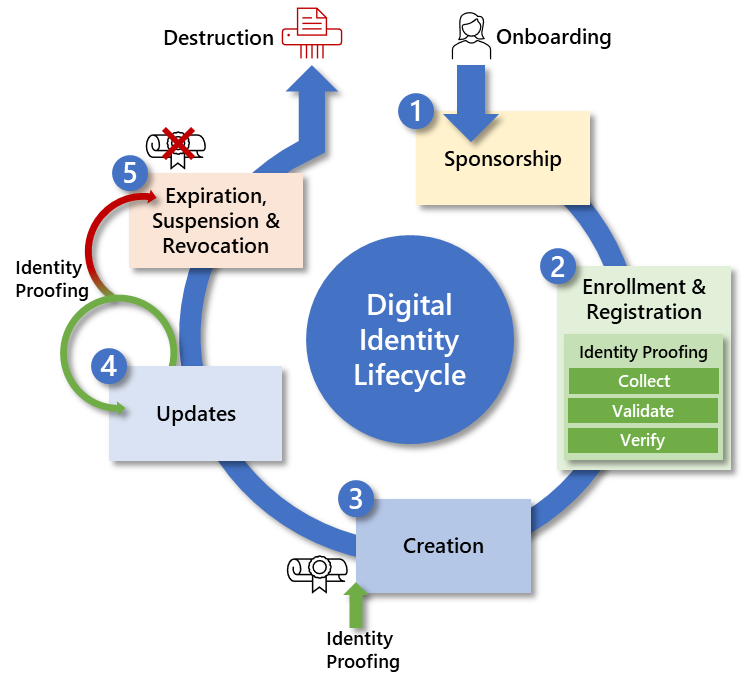

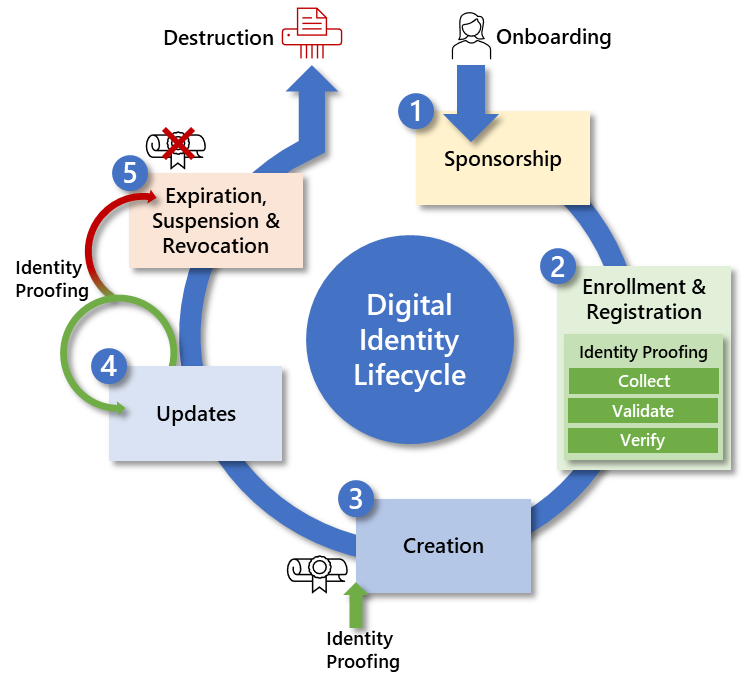

A digital identity is created based on a positive verification of an applicant from the identity proofing process. Identity proofing starts during the initial enrollment/registration process and may be updated at various stages of the digital identity lifecycle where life events warrant it. Figure 1 shows the Digital Identity Lifecycle and the events that take place during the creation, ongoing maintenance, and the suspension or expiration of a digital identity. 2 Identity proofing can be performed remotely via the Internet or in person at a physical building with individuals hired and trained to perform proper proofing.

Figure - Identity Proofing in the Digital Identity Life Cycle

Identity proofing is thought to be done once, at the time of enrollment/registration. But that may not be the only case and may be required at various stages of the digital identity lifecycle where life events warrant it. As illustrated in Figure 1, the following are the digital identity lifecycle processes:

-

Sponsorship: The onboarding process to obtain a digital identity. This process may require the applicant to either have or create an account with the CSP prior to sponsorship. This is the first step in the digital identity lifecycle.

-

Enrollment and Registration: The process through which an applicant applies to become a subscriber of the CSP and the CSP validates the applicant’s identity. This is generally done via an in-person or remote identity-proofing process.

-

Creation: After a successful Identity Proofing event, the CSP provisions a credential by binding the credential to the subscriber’s digital identity.

-

Updates: The act or process by which a requirement to be identity proofed after the initial digital identity is established. Examples of identity-proofing updates include:

-

Per policy, an organization may require identity proofing of their users every three years, such as a government employee who needs to renew the certificates on their smart card.

-

Change in name or gender may require the subscriber to be identity proofed again.

-

The subscriber may initially have been identity proofed at a lower assurance level but, based on required access to higher-risk transactions, the subscriber may be asked to be identity proofed at a higher level of assurance.

-

There are several scenarios, including times of emergency or transactions between strangers, when one may need to be identity proofed to ensure that that digital identity still belongs to that real-life person who was identity proofed at enrollment.

-

-

Suspension/Revocation: Revocation is the process of permanently changing the status of a credential to invalid (e.g., the credential has been compromised or the status of the sponsor has changed). There may also be an expiration of the credential bound to the subscriber, which may either trigger another identity-proofing event to renew the credential or surrender the credential housed on a smart card to the CSP. Reasons for suspending or revoking a credential include:

-

Lost/stolen device.

-

Death of the subscriber.

-

デジタル・アイデンティティはどのように作成される?

デジタル アイデンティティ は身元確認プロセスでの申請者の積極的検証によって作成されます。身元確認は初期の登録プロセスにおいて開始され、デジタル・アイデンティティのライフサイクルの様々なステージで更新される可能性があります。図1はデジタル・アイデンティティのライフサイクルと、新規作成、継続的なメンテナンス中、一時停止や失効中に発生するイベントを示しています。 2 身元確認はインターネット越しの遠隔で実行することも、物理的な建物で適切な確認をおこなうために雇用され、訓練された人物が対面で実施することもできます。

Figure - Identity Proofing in the Digital Identity Life Cycle

身元確認は登録時に一度しか実施されないと考えられています。しかし、そのときだけとは限らず、デジタル・アイデンティティを確認するライフ・イベントが発生するライフサイクルの様々な段階で必要とされます。図1で示したように、以下はデジタル・アイデンティティのライフサイクルの段階です:

-

身元保証(Sponsorship):デジタル・アイデンティティを取得する最初のプロセスです。このプロセスは、申請者がスポンサーシップの前にCSPでアカウントを保有したり、作成したりすることを要求するでしょう。

-

登録(Enrollment and Registration):申請者がCSPの登録者になることを申し込み、CSPが申請者のアイデンティティを確認するプロセスです。一般的に対面やリモートで実施される身元確認プロセスです。

-

作成(Creation):身元確認イベントの成功後、CSPは登録車のデジタル・アイデンティティにクレデンシャルをバインドすることでクレデンシャルを提供します。

-

更新(Updates):最初のデジタル・アイデンティティの確立後に身元確認が必要される行為やプロセスです。身元確認の更新の例には以下のものが含まれます:

-

ポリシーによりますが、組織はスマートカードの証明書を更新する必要がある政府職員のように3年ごとにユーザーの身元確認を要求するかもしれません。

-

氏名やジェンダーの変更は、登録者に再度身元確認を要求するかもしれません。

-

登録者は当初に低い保証レベルで身元確認したが、ハイリスクな取引に必要なアクセス権に基づいて、登録者はより高い保証レベルでの身元確認が要求されるかもしれません。

-

緊急時や見知らぬ人同士での取引など、いくつかのシナリオでは、デジタル・アイデンティティが登録時に身元確認された実在の人物のものであることを確認するために身元確認が必要になるかもしれません。

-

-

一時停止/無効化(Suspension/Revocation):無効化は永久的にクレデンシャルのステータスを失効へと変更するプロセスです(例 クレデンシャルが侵害された、または身元保証人の状態が変化した)。また、登録者にバインドされたクレデンシャルの有効期限が切れた場合には、クレデンシャルを更新するためにほかの身元確認イベントを実施するか、CSPにスマートカードに格納されているクレデンシャルを返却します。クレデンシャルの一時停止や無効化の理由には以下が含まれます:

-

デバイスの喪失/盗難。

-

登録者の死去

-

What is the difference Between In-Person Proofing and Remote Proofing?

In-person identity proofing is when individuals are required to present themselves and their documentation directly to a person. Remote identity proofing is used when individuals are not expected to present themselves or their documents in person and, instead, provide it online. In either case, this traditionally involves validating and verifying presented data against one or more corroborating authoritative sources of data.

対面での身元確認とリモートでの身元確認の違いは?

対面での身元確認は、個人が自分自身と身分証明書を直接人間に提示する必要がある場合です。リモートでの身元確認では、個人が自分自身と身分証明書を人間に提示することは期待されておらず、代わりにオンラインで提示する場合です。どちらの場合でも、提示されたデータを一つ以上の裏付けとなる権威のあるデータソースに対して確認、検証することが慣例となっています。

Why is remote identity proofing hard and what are the challenges?

Historically, IdPs/CSPs who offered remote identity proofing services typically relied on knowledge-based authentication (KBA), where applicants were asked static questions about themselves and expected to be the only ones to know the answers to such questions, such as job history, credit report data or credit history, their mother’s maiden name, their date of birth, etc. IDPs/CSPs used data collection companies, such as the credit bureaus, Lexis/Nexis, SEON Technologies, Silent Eight, and others, as authoritative sources of identity information to verify the applicant’s responses. If applicants responded correctly to these questions, the credit bureaus would provide a scoring to indicate the assurance of that identity based upon the answers provided. The CSPs, in turn, used those scores in determining the acceptable level of assurance that the identity was verified. However, due to recent data breaches, massive amounts of personally identifiable information (PII) have been stolen and made available from multiple sources, including those on the dark web. Reports of fraud activity clearly show that significant amounts of PII have fallen into the hands of criminals and are being used for identity-related crimes, such as stealing services, assets, or benefits. The recent Twitter, LastPass, and AT&T data breaches, as reported by the Identity Theft Resource Center, are good examples of these types of compromised identity data. 3 As a result, solely relying on the use of KBA is insufficient for corroborating an individual’s claimed identity.

Successful remote identity proofing is contingent on the user having technical knowledge of the process and what is needed to accomplish it successfully (e.g., the user has a smartphone and the ability to use it to capture images/pictures and has valid identification that can be verified with the issuing authority). Online remote identity proofing is difficult because the validation and verification process can be cumbersome and challenging. Identity documentation may not be available, or the documentation provided by the applicant may be insufficient. Further difficulties arise when not all applicants have a smartphone or government-issued identification card that can be remotely validated. Some may find the identity validation and verification process can be too time-consuming or difficult. This increased user friction causes applicants to get frustrated and abandon the service.

The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) released a remote identity proofing report that identified four out of six federal agencies that are still relying on PII-related KBA. 4 The GAO report cites high costs and implementation challenges for certain segments of the public as reasons why some agencies have not adopted alternative identity-proofing methods to KBA. For example, the lack of a mobile phone for some applicant populations was given as a key implementation challenge. Organizations still using KBA should evaluate the value of their KBA solutions and, where possible, replace them with a more dynamic KBA. Additionally, the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity, ENISA, which is dedicated to achieving a common level-high of cybersecurity across Europe, also published a remote I.D. proofing report in March 2021. 5 In their report, they’ve identified similar gaps with a lack of awareness and understanding of the remote proofing process, the variation in quality and completeness of identity evidence across the many European countries, and the desire to use physical presence as the benchmark, which, while tempting, cannot be reasonable when considering the variables introduced in remote proofing.

Over the last few years, there have been multiple government efforts to offer the public secure and private online access to participating government programs both here in the U.S. and abroad. The goal was to make managing government-provided benefits, services, and applications easier and more secure for the populations they were designed to serve. Whether agency applications and services would need to integrate with a single government authentication service is still in question. A single authentication entity for government services would require users to first be redirected to this central authentication service via secure protocols to register, be identity proofed, and assigned an authenticator (either remotely or in-person). Once the user has been identity proofed and acquired an authenticator, the authenticator could be presented to any Government online application or service that accepts them, provided they meet the required identity assurance level of that application or service. Gaining consensus across multiple agencies of the one government to use a common authentication service has proven to be much more difficult than anticipated.

Another remote proofing challenge is that there are too many misperceptions about why personal information, especially biometrics, is being requested and used. Many citizens do not trust the government to protect their personal information and question how it is being used. As a result, many people are reluctant to share their personal information for fear that the information will be used for more than the specified purposes. By not carefully explaining why data is being collected, how it is being used, and whether or not the data is stored or destroyed after remote identity proofing is complete, individuals may not provide the required information and will therefore fail remote identity proofing.

According to concerns expressed by the GAO report, additional work is needed to ensure that a fraudulent image, such as a photo of a mask, is not being provided in lieu of a live image — a threat known as a “presentation attack.” Keeping up with ever-evolving threats to remote identity proofing and implementing the proper security controls to mitigate those threats is an ongoing challenge.

Challenges with remote identity proofing extend to other countries as well. The United Kingdom (U.K.) was among the first to try remote identity proofing, but it has been plagued with performance issues. One of their key problems was centered around the datasets used by the identity providers when trying to confirm a user’s identity. Applicant data used for verification did not match what was on the government’s systems, resulting in the U.K. government not being able to create and manage the system. Due to these problems, private industry is taking over the effort with the first task addressing the issue of the mismatched datasets used by the identity providers.

なぜリモートでの身元確認が難しいのか、課題は何か?

歴史的に、リモート身元確認サービスを提供するIdP/CSPは一般的に 知識ベース認証(KBA) に依存しており、申請者は自分自身に関する静的な質問をされ、職歴、信用報告データや信用履歴、母親の旧姓、誕生日などの質問に対する回答を知っている唯一の人物であることが期待されます。IdP/CSPは申請者の回答を検証するため、信用情報機関やLexis/Nexis、SEON Technologies、Silent Eightなどのようなデータ収集企業をアイデンティティ情報の権威あるソースとして利用しました。申請者が質問に正しい回答をした場合、信用情報機関は提供された回答に基づいてアイデンティティの保証を示すスコアを提供します。次に、CSPはアイデンティティが検証された保証の受け入れレベルを決定するため、これらのスコアを利用します。しかし、昨今のデータ侵害によって大量の個人識別情報(PII)が盗まれ、ダークウェブを含む複数のソースから入手可能になっています。詐欺行為に関する報告書では大量のPIIが犯罪者の手に落ち、サービスや資産、利益の盗難のようなアイデンティティに関連した犯罪に使用されていることがはっきりと述べられています。Identity Theft Resource Centerが報告した直近のTwitter、LastPassおよびAT&Tのデータ侵害はアイデンティティ情報の侵害に関する好例です。 3 つまるところ、KBA利用だけに依存することは、個人の主張するアイデンティティの保証には不十分です。

リモートでの身元確認の成功は、ユーザがプロセスに関する技術的な知識とプロセスの完了に必要なものを有しているかに左右される(例えば、ユーザがスマートフォンを所有しており、画像取得や写真撮影をおこなうためにスマートフォンを利用する能力があり、発行した権威機関によって検証できる正当な身分証明書を所持している)。オンラインのリモートでの身元確認は、確認と検証のプロセスが面倒で困難であることから難易度が高いです。身分証明書が利用できない場合や、申請者が提示した身分証明書が不十分な場合もあります。さらに、すべての申請者がスマートフォンや政府発行のリモートで正当性確認ができる身分証明カードを有していないことが難易度を高くします。一部の人々は、アイデンティティの確認と検証のプロセスが時間の無駄と感じたり、難しいと感じたりするかもしれません。このようなユーザーが感じる摩擦の増加は申請者がフラストレーションをためたり、サービスを放棄してしまったりします。

米国会計検査院(GAO)はリモートでの身元確認に関する報告書をリリースし、6つの連邦機関のうち4つは未だにPIIに関連したKBAに依存していると述べています。 4 GAOの報告書は、一部の機関がKBAに代わる身分確認を採用していない理由としてコストの高さと特定の一般市民にとっての導入の難しさを挙げています。例えば、一部の申請者にとって携帯電話を持っていないことは導入の難しさとなります。KBAの利用を継続している組織はKBAソリューションの価値を評価し、できればより動的なKBAに置換するべきです。さらに欧州連合(EU)のサイバーセキュリティ機関であるENISA、ヨーロッパ全体で共通レベルの高いサイバーセキュリティを達成することを目的とする、も2021念3月にリモートでの身元確認に関する報告書を公開しました。 5 この報告書では同じようにリモートでの身元確認プロセスの認識と理解の欠如についてのギャップがあること、多くのヨーロッパ諸国間で身分証明の質と完全性についてバラツキがあることとベンチマークとして物理的な存在を使いたい、これは魅力的ですがリモートでの身元確認の導入でひるような変数を考慮すると合理的とは言えません、という願望を指摘しています。

ここ数年、アメリカ国内外を問わず、参加する政府プログラムへのパブリックで安全かつプライベートなオンラインアクセスを国民に提供しようとする政府の取り組みが複数おこなわれてきました。その目的は、政府が提供する給付金、サービス、アプリケーションの管理を、それらの提供先とされている人々にとってより簡単かつ安全にすることでした。政府機関のアプリケーションやサービスが単一の政府認証サービスと統合する必要があるかどうかは、まだ疑問です。政府サービスに単一の認証エンティティを使用する場合、ユーザは、まず安全なプロトコルを介してこの中央認証サービスにリダイレクトされ、登録し、(リモートまたは対面で)身元確認されて認証器を割り当てられる必要があります。ユーザが身元確認され、認証器を取得すると、認証器が政府のオンラインアプリケーションまたはサービスが必要するアイデンティティ保証レベルを満たしていれば、アプリケーションまたはサービスに認証器に提示することができます。共通の認証サービスを利用するために、1つの政府の複数の機関にまたがる同意の取得することは、予想以上に困難であることがわかっています。

もう一つのリモート身元確認の課題は、個人情報、特にバイオメトリクスがなぜ要求され使用されるのかについて、あまりにも多くの誤解があることです。多くの国民は、政府が自分の個人情報を保護することを信用しておらず、それがどのように使用されているかに疑問を抱いています。その結果、多くの人々は、情報が指定された目的以上に利用されることを恐れ、個人情報を共有することに消極的になっています。データが収集される理由、データが利用される方法およびリモート身元確認が完了した後でデータが保存または破棄されるかどうかを注意深く説明しないことにより、個人は必要な情報を提供せず、したがってリモート身元確認が失敗する可能性があります。

GAOの報告書で指摘された懸念によると、実写画像の代わりに変装写真のような偽造画像の提供(いわゆる「入力データ攻撃」)がおこなわれていないことを確認するための追加作業が必要です。リモート身元確認に対する進化し続ける脅威に対応し、それらの脅威を軽減する適切なセキュリティ管理を実施することは、継続的な課題です。

リモート身元確認の課題は他の国にも及んでいます。英国(U.K.)はリモート身元確認を最初に試みた国の1つであるが、パフォーマンスの問題に悩まされてきました。主な問題の1つは、ユーザーのアイデンティティを確認しようとするときにアイデンティティ・プロバイダーが使用するデータセットに関するものでした。検証に使用される申請者データが政府のシステム上にあるものと一致しなかったため、英国政府はシステムを作成および管理することができませんでした。このような問題のため、民間企業がこの取り組みを引き継ぎ、最初の課題としてアイデンティティ・プロバイダーが使用するデータセットの不一致の問題に取り組んでいます。

Summary

Today, many organizations and government agencies rely heavily on being able to accurately identify, credential, monitor, and manage user access to information and information systems across their enterprise to ensure they know who is accessing their data. There are numerous situations where it is important to reliably establish an association of a digital identity with a real-life subject. Identity proofing establishes that a person is who they say they are based on the validity of one or more pieces of identity evidence. The more due diligence incorporated into the identity-proofing process, the higher the confidence that the applicant is who they claim to be.

Historically, those who offered remote identity proofing services typically relied on knowledge-based authentication (KBA), where applicants were asked static questions about themselves (such as their mother’s maiden name, the street they grew up on, or their father’s date of birth) and expected to be the only one to know the answers to such questions. However, vast amounts of data about an individual have been stolen in data breaches and are readily available to purchase online. This stolen data can be used by fraudsters to then obtain access to your bank account, receive your stimulus check, or your tax returns. It is due to this high increase in stolen identities that organizations are finding that they no longer trust that digital identity and must improve their remote identity-proofing efforts to more effectively thwart fraudsters.

The use of online remote identity proofing services is difficult because the validation and verification process can be cumbersome and challenging. Identity documentation may not be available, or the documentation provided by the applicant may be insufficient. Further difficulties arise when not all applicants have a smartphone or government-issued identity card that can be remotely validated. Some may find the identity validation and verification process can be too time-consuming or difficult. This increased user friction causes applicants to get frustrated and abandon the service.

まとめ

今日、多くの組織や政府機関は、誰がデータにアクセスしているかを確実に把握するために、 企業全体の情報や情報システムへのユーザー・アクセスを正確に識別、認証、監視および管理できることに大きく依存しています。デジタル・アイデンティティと現実の対象との関連付けを確実に確立することが重要な状況は数多くあります。身元確認は、1つまたは複数の身分証明の妥当性に基づいて、その人が本人であることを立証します。身元確認プロセスにデュー・ディリジェンスが組み込まれていればいるほど、申請者が本人であるという信頼性が高くなります。

歴史的に、リモート身元確認サービスは一般的に、知識ベース認証(KBA)に依存しており、申請者は自分自身に関する静的な質問(母親の旧姓、育った通りの名前または父親の生年月日など)をされ、そのような質問の答えを知っているのは本人だけであることが期待されていた。しかし、個人に関する膨大な量のデータがデータ侵害によって盗まれ、オンラインで簡単に購入できるようになっています。盗まれたデータが詐欺師によって利用され、銀行口座にアクセスしたり、給付金の小切手や還付金を受け取ったりするのに使われる可能性があります。このように盗まれたアイデンティティが急増しているため、組織はデジタル・アイデンティティを信用できなくなり、詐欺師をより効果的に阻止するためにリモート身元確認の改善に取り組まなければならなくなっています。

オンライン・リモート身元確認サービスの利用は、正当性確認および検証プロセスが面倒で困難であることから難易度が高いです。身分証明書が利用できない場合や、申請者が提示した身分証明書が不十分な場合もあります。さらに、すべての申請者がリモートで検証できるスマートフォンまたは政府発行のアイデンティティカードを所持しているわけではないことで難易度は高くになります。また、本人確認や検証のプロセスに時間がかかりすぎたり、難しいと感じたりする人もいます。このようなユーザーが感じる摩擦の増大により、申請者はフラストレーションを感じ、サービス利用を放棄してしまいます。

Authors

Lorrayne Auld

Principal Cybersecurity Engineer, MITRE Corporation

Lorrayne has over 25 years of experience in the area of identity and access management, secure web, portal, and Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) technologies supporting the Federal Government. She has worked both as a hands-on integrator and as a cybersecurity engineer providing guidance to the government. She has helped multiple agencies with their Identity, Credential, and Access Management (ICAM) strategies, implementation guidance, and best practices.

Lorrayne serves as the focal point for researching, understanding, and applying ICAM emerging technologies while ensuring ongoing growth within this area. She also serves as the senior advisor to the ICAM capability area as well as a mentor to junior staff. She has spoken at conferences on higher assurance identity proofing and next-generation authentication technologies. Lorrayne is a member of Kantara, IDPro, Women in Identity, and the FIDO Alliance.

Sandy Christopher

Senior Communications Advisor, MITRE Corporation

Building on 20+ years of leading communication and change, Sandy delivers holistic communication programs that measurably engage stakeholders and achieve business goals. Throughout her career, Sandy has worked with executive leadership to create strategic communication plans that align employees with the priorities of the organization. She is an innovative problem solver with extensive domestic and international communication experience on a wide range of issues, including organizational change, crisis communications, healthcare, information technology, ethics, operational risk, quality, deregulation of the utility industry, human resources, environmental, and financial services.

Russ Reopell

Principal Cybersecurity Engineer, MITRE Corporation

With over 25 years of experience in identity and access management, Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) technologies, and web services focused on identity, authentication, and authorization, Mr. Reopell has supported the Federal Government, Department of Defense, and Telecommunication companies. He began his career as a programmer and quickly became involved in the design, development, integration, and testing of various Air Force and Naval support systems. In the early 80s, he began working on information security systems and helped deploy security solutions in federal and commercial spaces until finally focusing on Identity, Credential, and Access Management (ICAM) strategies, implementation guidance, and best practices.

Russ worked closely with other MITRE staff and served as MITRE’s ICAM Capability Area Lead for many years. Russ was the go-to person across MITRE to assist with or guide staff in the design and integration of ICAM capabilities to the many sponsors MITRE supports. He is responsible for researching, understanding, and applying ICAM emerging technologies and helped to grow work in this ever-evolving area. Russ is a member of IDPro and enjoys mentoring junior staff to increase their knowledge as well as pique their curiosity about the many exciting innovations in the ICAM space.

-

Dow Jones, “Understanding the Steps of a “Know Your Customer” Process,” Risk and Compliance Glossary, n.d., https://www.dowjones.com/professional/risk/glossary/know-your-customer/ (accessed 27 March 2023). ↩ ↩2

-

For more on the digital identity lifecycle, see Cameron, A. & Grewe, O., (2022) “An Overview of the Digital Identity Lifecycle (v2)”, IDPro Body of Knowledge 1(7). doi: https://doi.org/10.55621/idpro.31 ↩ ↩2

-

Identity Theft Resource Center, 2022 Data Breach Report , January 2023. https://www.idtheftcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/ITRC_2022-Data-Breach-Report_Final-1.pdf (accessed 24 March 2023). ↩ ↩2

-

U.S. Government Accountability Office (U.S. GAO), DATA PROTECTION Federal Agencies Need to Strengthen Online Identity Verification Processes , May 2019. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-19-288-highlights.pdf (accessed24 March 2023). ↩ ↩2

-

European Union Agency for Cybersecurity, REMOTE ID PROOFING Analysis of methods to carry out identity proofing remotely, March 2021. https://www.enisa.europa.eu/publications/enisa-report-remote-id-proofing (accessed 24 March 2023). ↩ ↩2