IDPro Body of Knowledgeの翻訳メモです。

元記事:https://bok.idpro.org/article/id/44/

IDPro Body of Knowledgeの翻訳メモのトップページ

Abstract

This introductory article on privacy and compliance in the consumer IAM domain sets the foundation for subsequent sections on privacy within the IDPro Body of Knowledge, providing an overview of a variety of topics, including definitions of privacy, different approaches to privacy in the consumer sector versus the workforce environment, and more.

Keywords: Consent, Privacy, Privacy by Design, Data Protection, Consumer, Compliance

概要

消費者向けのIAM領域におけるプライバシーとコンプライアンスに関するこの入門記事は、IDPro Body of Knowledgeにおけるプライバシーに関する後続のセクションの基礎となるもので、プライバシーの定義、消費者部門と労働環境におけるプライバシーへのアプローチの違いなど、さまざまなトピックの概要を提供します

Keywords: 同意, プライバシー, プライバシー・バイ・デザイン, データ保護, 消費者, コンプライアンス

© 2022 IDPro, Clare Nelson

Updated by the IDPro Body of Knowledge Committee

To comment on this article, please visit our GitHub repository and submit an issue .

Disclaimer

This article should not be considered legal advice. Identity programs that support data protection and privacy as a fundamental human right are complex and highly technical. Many of the data protection and privacy laws in countries around the world are evolving and open to interpretation. Please consult your organization’s legal counsel for specific advice appropriate to your jurisdiction

Related Sections in the IDPro Body of Knowledge

Please refer to other forthcoming sections of the IDPro Body of Knowledge 1 for supporting and complementary information, notably:

-

Andrew Cormack’s “An Introduction to the GDPR” 2

-

Andrew Hindle’s “Impact of GDPR on Identity and Access Management” 3

-

“Terminology in the IDPro Body of Knowledge” 4

Introduction to Privacy and Compliance for Consumers

Identity professionals, including enterprise solution architects, data scientists working in marketing, privacy professionals, product managers, and strategists at data brokers, have an opportunity to improve privacy plus compliance with data protection regulations and laws for consumer-facing applications. Several critical issues drive the need for improvement:

-

Unique identification of a natural person, such as a consumer, is easier than ever before. The smallest shred of digital exhaust, physical actions, or attributes can be collected, correlated via machine learning, and analyzed to identify a unique consumer or household with sufficient probability.

-

Consent is broken. The complexity of privacy notices, and the length of privacy policies that are rarely read, lead to a pattern of ineffectiveness, the illusion of choice, burden on the consumer, and the eventual agreement to broad terms which may not have limits or may be modified at any future date with only limited or obscure notice. As privacy and law expert Daniel Solove has stated, “Giving individuals more tasks for managing their privacy will not provide effective privacy protection.” 5 There is a growing realization that privacy laws should make stewardship of data the responsibility of the data controller and/or data processor, not the consumer.

-

Data privacy laws are years behind technology innovations, and the gap is expanding. Privacy laws cannot keep pace with technological advancements and are years behind in catching up to the 4,000 data brokers and analytics companies that collect personal data across all touchpoints, many of which are adding muscle with machine learning. Many marketing companies, plus some of the world’s largest organizations, are seeking alternatives to third-party cookies in order to be able to continue to identify consumers, all within the porous guidelines of current privacy law.

-

Anonymity does not exist, and pseudonymization provides weak protection

-

For example, researchers have proved that based on geolocation alone, anonymity does not exist. 6

-

Similarly, researchers posit that it is becoming easier to re-identify a person:

- Once released to the public, data cannot be taken back. As time passes, data analytic techniques improve, and additional datasets become public that can reveal information about the original data. It follows that released data will get increasingly vulnerable to re-identification—unless methods with provable privacy properties are used for the data release. 7

-

Communications of the ACM recently published an article on anonymity that confirms what many mathematicians have always known: there is still a pattern in the anonymous data and a way to de-anonymize it. 8

- “Anonymized data can never be totally anonymous: anonymization is not sufficient for private companies to avoid conflicts with laws such as Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation, and the California Consumer Privacy Act.” 9

-

The scope of privacy for what the GDPR calls natural persons keeps expanding because the ability to uniquely identify a human being with the tiniest bit of digital exhaust or trace of online or offline behavior keeps expanding. Where a person ate lunch, the way they moved their mouse to find the cursor, what they said to a service representative over the phone in light of the warning, “this call may be recorded for quality purposes,” what they bought online, their device and all its related attributes, or where they bought gas may be sufficient to uniquely identify a natural person. Long gone are the days when name, address, social security number, and date of birth were the only identifiers. Now, we need to protect massive collections of personal and related data in order to provide privacy for consumers.

消費者のためのプライバシーとコンプライアンスの入門

企業のソリューションアーキテクト、マーケティングに携わるデータサイエンティスト、プライバシーの専門家、プロダクトマネージャー、データブローカーのストラテジストなどを含むアイデンティティの専門家は、プライバシーの改善に加えて消費者向けアプリケーションのデータ保護規制や法律に準拠する機会があります。いくつかの重要な問題が、改善の必要性を促します:

-

消費者のような 自然人 の一意的な識別は、かつてないほど容易になっています。デジタルの排気ガス、物理的な行動または属性の最も小さな断片を収集し、機械学習を介して相関させ、充分な確率で一意の消費者または世帯を識別するために分析することができます。

-

同意は破綻しています。プライバシーに関する通知の複雑さや、ほとんど読まれることのないプライバシーポリシーの長さは、効果がなく、選択を錯覚させ、消費者の負担、制限のない広範な規約への最終的な同意、あるいは限られた、あるいは不明瞭な通知のみで将来の任意の日に変更される可能性のある規約への最終的な同意というパターンにつながります。プライバシーと法律の専門家であるDaniel Soloveが述べているように、「個人にプライバシーを管理するためのタスクを増やしても、効果的なプライバシー保護にはなりません」。 5 プライバシー法は、データの管理責任を消費者ではなく、データ管理者および/またはデータ処理者に負わせるべきだという認識が広まっています。

-

データプライバシー法は技術革新に何年も遅れており、その差は拡大する一方です。プライバシー法は技術の進歩に追いつくことができず、あらゆるタッチポイントで個人データを収集する4,000社のデータブローカーや分析会社、その多くは機械学習で力をつけています、に追いつくのは何年も遅れています。多くのマーケティング企業や世界最大級の組織は、現行のプライバシー法の厳しいガイドラインの範囲内で消費者を識別し続けるために、サードパーティCookieに代わるものを求めています。

-

匿名性は存在せず、仮名化による保護は脆弱

-

例えば、研究者はジオロケーションだけでは匿名性が存在しないことを証明しています。 6

-

同様に、研究者は、人物の再識別が容易になりつつあると仮定しています:

- 一度公開されたデータは元に戻すことができません。時間が経つにつれ、データ分析技術は向上し、元のデータに関する情報を明らかにすることができるデータセットが追加で公開されるようになる。そのため、公開されたデータはプライバシーを証明できる方法を用いない限り、再識別に対してますます脆弱になります。 7

-

Communications of the ACM は最近、匿名性に関する論文を発表し、多くの数学者が常に知っていたことを確認しました:匿名のデータにはまだパターンがあり、それを脱匿名化する方法があるのです。 8

- 「匿名化されたデータは完全に匿名化されることはない。民間企業が欧州一般データ保護規則やカリフォルニア州消費者プライバシー法などの法律との衝突を回避するには、匿名化だけでは不十分です。」 9

-

GDPRが 自然人 と呼ぶものに対するプライバシー範囲が拡大し続けるのは、ほんのわずかなデジタルの排気ガスやオンラインまたはオフラインの行動痕跡で人間を一意に特定できる能力が強化され続けているからです。個人の昼食を食べた場所、カーソルを見つけるためのマウスの動かし方、「この通話は品質保持のために記録される可能性があります」という警告のあとに電話でサービス担当者に言ったこと、オンラインで買ったもの、デバイスとその関連属性すべて、あるいはガソリンの購入場所は、自然人を一意に特定するのに充分な場合があります。名前、住所、社会保障番号そして生年月日が唯一の識別子であった時代はとうに過ぎ去りました。今や消費者にプライバシーを提供するために、膨大な数の個人情報および関連データを保護する必要があります。

Terminology and Acronyms

-

Consent - permission for something to happen or agreement to do something

-

GDPR – General Data Protection Regulation 10

-

CCPA – California Consumer Privacy Act 11

-

Natural Person – an individual human being

-

NY SHIELD Act – New York “Stop Hacks and Improve Electronic Data Security” Act 12

-

Privacy - an abstract concept with no single, common definition

Scope

The lofty goal of this section on Privacy and Compliance for Consumers is to present a global perspective. However, the initial release of this section is more focused on the GDPR, CCPA, and NY SHIELD Act with a light coverage of China and the rest of the world. As noted below in the Resources section, the International Association of Privacy Professionals (IAPP) is an excellent source of information for immediate, current, comprehensive global coverage.

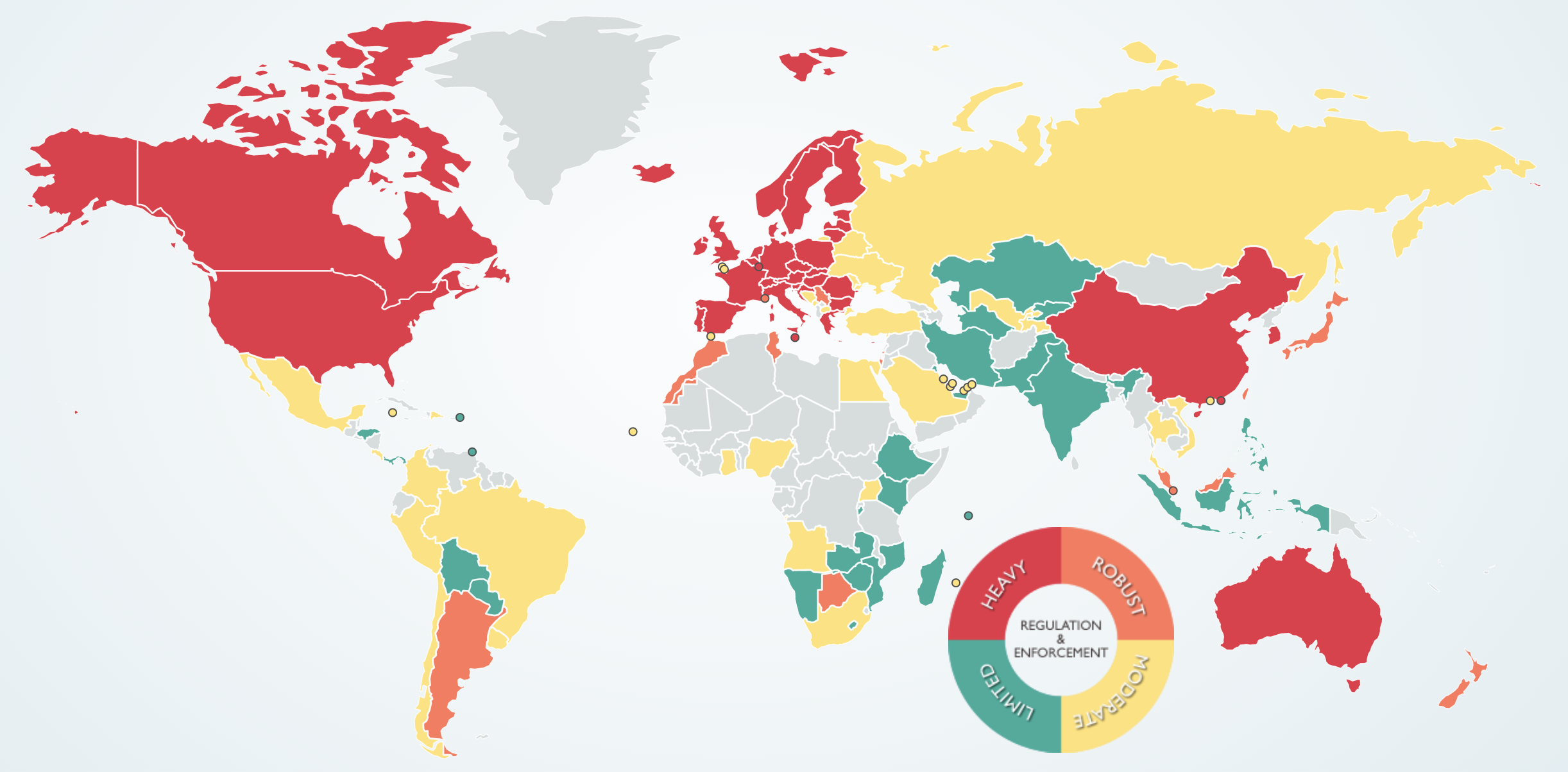

Requirements for data protection and associated privacy regulations are increasing around the world. On March 21, 2020, the NY SHIELD Act went into effect, and China is working on updated privacy law. Most are familiar with the GDPR and CCPA. 13 The figure below highlights global regulation and enforcement as heavy, robust, moderate, or limited.

スコープ

消費者のためのプライバシーとコンプライアンス に関するこのセクションの高い目標は、グローバルな視点を提示することです。しかし、このセクションの最初では、GDPR、CCPAおよびNY SHIELD法に着目し、中国やその他の地域については軽く取り上げています。後述のリソースセクションにあるように、国際プライバシー専門家協会(IAPP)は即時、最新、包括的な全世界をカバーした情報を提供する優れた情報源です。

データ保護と関連するプライバシー規制の要件は、世界中で増加しています。2020年3月21日にはNY SHIELD法が施行され、中国はプライバシー法の更新に取り組んでいます。GDPRとCCPAについては、ほとんどの人がよく知っています。 13 下図は、グローバルな規制と執行を「厳格(heavy)」、「堅牢(robust)」、「中程度(moderate)」、「限定的(limited)」に分類したものです。

In this section, we consider personal data obtained, stored, or tracked through a variety of mechanisms, including cookies, electronic communications (Internet, email, messaging, apps), Wi-Fi, telephone, and Internet-of-Things (IoT). All of this data can be used to identify a unique individual and may be considered private, requiring protection as a fundamental human right . The first recital of the GDPR states that data protection is a fundamental right according to the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TEFU) . 15 , 16 The United Nations adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, a global mandate for privacy, as articulated in Article 17: 17

No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honour and reputation. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks.

| EU GDPR | EU ePrivacy Directive | US CCPA, NY SHIELD , other | California, Oregon IoT Security Law; Singapore, others | Rest of the World | |

| What is covered? | Personal data, cookie consent | Cookies, Internet, email, messaging, phone; tracking mechanisms, right of confidentiality | Personal data, household data under CCPA | Any connected device; has an IP address or Bluetooth address | China - none; APEC - Personal Information* |

Table 1. Beyond GDPR: Personal Data Includes Cookies, Phone, and IoT

*According to the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Privacy Framework , Personal Information is any information about an identified or identifiable individual. 18

The GDPR is closely related to the ePrivacy Directive. The ePrivacy Directive is soon to be replaced with the ePrivacy Regulation. The GDPR and ePrivacy Regulation are both parts of the data protection reform in the EU; where there is overlap, the ePrivacy Regulation overrides the GDPR, notably for cookies and electronic communication. 19

IoT law is covered below. Note that emerging laws seek first to get rid of embedded or hardcoded passwords. When an IoT device ships with the password already installed from the manufacturer, this makes it easy to breach privacy as well as to create botnet malware.

このセクションでは、Cookie、電子通信(インターネット、電子メール、メッセージング、アプリ)、Wi-Fi、電話、IoTなど、さまざまなメカニズムを通じて取得、保存、追跡される個人データについて考察します。これらのデータはすべて、個人を識別するために使用することができ、基本的人権として保護を必要とする個人情報とみなされる可能性があります。GDPRの第一項には、欧州連合基本権憲章 および欧州連合機能条約(TEFU) に従い、データ保護が基本的人権であると明記されています。 15 , 16 国連は1948年に世界人権宣言を採択し、第17条に明記されているように、プライバシーに関する世界的な義務となっています: 17

何人も、自己の私事、家族、家庭若しくは通信に対して、ほしいままに干渉され、又は名誉及び信用に対して攻撃を受けることはない。人はすべて、このような干渉又は攻撃に対して法の保護を受ける権利を有する。

| EU GDPR | EU ePrivacy Directive | US CCPA, NY SHIELD , 他 | California, Oregon IoT Security Law; Singapore, others | Rest of the World | |

| 何がカバーされている? | 個人データ, Cookie同意 | Cookie, インターネット, Eメール, メッセージ, 電話; 追跡メカニズム, 機密保持の権利 | 個人データ, CCPAの下の世帯データ | 接続されたデバイス; IPアドレスまたはBluetoothアドレスを持っているもの | 中国 - なし; APEC - 個人情報* |

Table 1. Beyond GDPR: Personal Data Includes Cookies, Phone, and IoT

*アジア太平洋経済協力(APEC)プライバシーフレームワークによると、個人情報とは、特定された、または特定可能な個人に関する情報です。 18

GDPRは、eプライバシー指令と密接に関連しています。eプライバシー指令はまもなくePrivacy規則に置き換えられます。GDPRとePrivacy規則は、どちらもEUのデータ保護改革の一部です。重複する部分がある場合、特にCookieと電子通信に関しては、ePrivacy規則がGDPRを上書きします。 19

IoT法については、以下で説明します。新しい法律では、埋め込まれたパスワードやハードコードされたパスワードを最初に取り除こうとすることに注意してください。製造元からパスワードがインストールされた状態でIoTデバイスが出荷されると、プライバシーの侵害やボットネット・マルウェアの作成が容易になります。

Setting the Stage

Scholars and privacy experts, including Hartzog, Zuboff, Schneier, and Maler, set the stage for examining these topics and beyond.

舞台準備

Hartzog、Zuboff、Schneier、Malerなどの学者やプライバシーの専門家が、これらのトピックとそれ以外を検討するための舞台を提供します。

Hartzog

Woodrow Hartzog is a Professor of Law and Computer Science at Northeastern University, and among other roles is an Affiliate Scholar at Stanford Law School for Internet and Society. In April 2019, Hartzog co-authored The Pathologies of Digital Consent with Neil Richards, where they discuss defects that consent models can suffer, including: 20

-

Unwitting consent

-

Coerced consent

-

Incapacitated consent

These consent defects are a far cry from the gold standard of knowing and voluntary consent . Hartzog and Richards conclude:

The over-use of consent in the digital context, combined with limited legal policing of the sufficiency of consent, has allowed great fortunes to be created on the basis of personal data, but it has also exposed consumers to data breaches, identity theft, and a surveillance economy unprecedented in human history, one which stretches the very notion of “consent” to say that it was ever actually agreed to.

More fundamentally, the manufacturing of consent by exploiting consent’s pathologies has diminished the trust in our digital environment that is the key ingredient toward a better future. We can do better, but in order to do so, we need to recognize the pathologies of consent and limit consent to the contexts in which it is most justified. Going forward, we must rely on strategies other than fictive, manufactured, or coerced consent to minimize the risks and harms of our information economy if we seek to take advantage of its benefits in a sustainable, ethical, and progressive way.

These consent issues are discussed further in subsequent sections, including a proposed solution or theory of consumer trust as an alternative to an over-reliance on increasingly pathological models of consent.

Hartzog

Woodrow Hartzogは、ノースイースタン大学の法学およびコンピュータサイエンスの教授であり、その他の役割として、スタンフォード大学法学部のインターネットと社会に関するアフィリエイト・スカラーを務めています。2019年4月、HartzogはNeil Richardsと共著で The Pathologies of Digital Consent を執筆し、同意モデルが被りうる欠陥について以下のように論じています: 20

-

無意識のうちに同意している

-

強制的な同意

-

無力な同意

このような同意の欠陥は、 知っていて自発的に同意するというゴールドスタンダード からは程遠いものです。HartzogとRichardsはこう結論付けている:

デジタルの文脈での同意の乱用は同意の充分性に関する限定的な法的取り締まりと相まって、個人データを基にした巨万の富の創造を可能にしましたが、同時に消費者をデータ漏洩、個人情報の盗難、人類史上前例のない監視経済にさらし、「同意」という概念そのものを実際に同意されていたと言えるかわからないものにしています。

より根本的には、同意の病理を悪用した同意の製造が、より良い未来に向けた重要な要素であるデジタル環境に対する信頼を低下させているのです。しかし、そのためには、同意の病理を認識し、同意を最も正当化される文脈に限定する必要があります。今後、持続可能で倫理的かつ進歩的な方法で情報経済の恩恵を受けようとするならば、リスクと害を最小化するために、架空の、捏造されたまたは強制された同意以外の戦略に頼らなければなりません。

このような同意の問題については後続のセクションでさらに議論し、ますます病的な同意のモデルへの過度な依存の代替となる消費者の信頼に関する解決策や理論の提案もおこないます。

Zuboff

In her recent, award-winning book, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future and the New Frontier of Power , Harvard’s Shoshana Zuboff clearly articulates her well-researched assertion that we live in a state of surveillance capitalism. Zuboff’s message is clear:

“Surveillance capitalism unilaterally claims human experience as free raw material for translation into behavioural data.

-

Although some of these data are applied to service improvement, the rest are declared as a proprietary behavioural surplus, fed into advanced manufacturing processes known as ‘machine intelligence’, and fabricated into prediction products that anticipate what you will do now, soon, and later.

-

Finally, these prediction products are traded in a new kind of marketplace that I call behavioural futures markets.

-

Surveillance capitalists have grown immensely wealthy from these trading operations, for many companies are willing to lay bets on our future behaviour.” 21

Zuboff

最近出版され、受賞した The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future and the New Frontier of Power の中でハーバード大学のShoshana Zuboffは、私たちが 監視資本主義の時代 に生きているというよく研究された主張を明確に述べています。Zuboffのメッセージは明快です:

「監視資本主義は、人間の経験を行動データに変換するための自由な原料であると一方的に主張している。

-

これらのデータの一部はサービス改善に利用されますが、残りは独自の行動剰余金として宣言され、「機械知能」と呼ばれる高度な製造プロセスに投入され、あなたが今、直近そして将来に何をするのかを予測する製品として製造されます。

-

最後に、これらの予測商品は、私が行動的先物市場と呼んでいる新しい種類の市場で取引されています。

-

多くの企業が私たちの将来の行動に賭けようとしているため、監視資本はこうした取引業務によって莫大な富を築いてきました。」 21

Schneier

Zuboff’s 2019 book on surveillance capitalism makes Bruce Schneier’s 2015 book, Data and Goliath: The Hidden Battles to Collect Your Data and Control Your World, pale in comparison. Consumers are left wondering, “Why didn’t you tell me it was so bad?” because Schneier does not provide the chilling detail about how far surveillance and collection of behavioral surplus have advanced. Zuboff’s words are even reflected in marketing messages of leading “data protection” vendors, “Privacy is the right of an individual to be free from uninvited surveillance.” 22

Schneier

監視資本主義に関するZuboffの2019年の本は、Bruce Schneierの2015年の本、 Data and Goliath: The Hidden Battles to Collect Your Data and Control Your World と比較になりません。Schneierは監視と行動余剰の収集がどこまで進んでいるのかについてゾッとするほど説明していないため、消費者は「なぜそんなにひどいことを教えてくれなかったのか?」と思うことになります。Zuboffの言葉「プライバシーとは、招かれざる監視から解放される個人の権利である」は、大手「データ保護」業者のマーケティングメッセージにまで反映されています。 22

Maler

In her 2018 Identiverse talk, Don’t Pave Privacy Cow Paths: Retool Consent for the New Mobility, ForgeRock CTO, then-VP Innovation and Emerging Technology, Eve Maler describes why “Consent doesn’t scale for the requirements of email, laptops, and browsers, never mind mobile devices and applications.

- How much worse is the situation going to get as connected vehicles become an ever-bigger part of consumers’ lives and an ever more significant integration point for every industry?” Maler establishes the “New Mobility as a critical scenario for examining consumer requirements for trust, regulatory requirements for privacy, how consent experiences and consent management must adapt, and how we can begin to meet these challenges.” 23

Maler’s words were prescient because, in the rush to implement consent for GDPR compliance, many companies have simply paved cow paths. Her talk describes how to refactor consent to accommodate today’s architectural requirements for asynchronicity, automation, and abstraction.

Maler

2018年のIdentiverseの講演Don’t Pave Privacy Cow Paths: Retool Consent for the New Mobilityにて、ForgeRockのCTO(当時のイノベーションおよびエマージングテクノロジーの統括責任者)Eve Malerは、その理由を次のように説明しています。「同意は、電子メール、ラップトップ、ブラウザの要件に合わせて拡張することはできません。モバイルデバイスやアプリケーションを気にする必要はありません。

- コネクテッド・ビークルが消費者の生活の中でこれまで以上に大きな部分を占め、あらゆる業界にとってこれまで以上に重要な統合ポイントになるにつれ、状況はどれほど悪化するのでしょうか?」 「新しいモビリティは、トラストに関する消費者の要件、プライバシーに関する規制要件、同意エクスペリエンスと同意管理をどのように適応させる必要があるか、そしてこれらの課題にどのように対応し始めることができるかを検討するための重要なシナリオです。」とMalerは述べています。 23

Malerの言葉には先見の明がありました。なぜなら、GDPRコンプライアンスへの同意の実装を急ぐあまり、多くの企業が単純に牛の道を舗装してしまったからです。彼女の講演では、非同期性、自動化および抽象化に関する今日のアーキテクチャ要件に対応するために同意をリファクタリングする方法について説明しています。

What is Privacy?

Privacy is an abstract concept with many definitions and even more potential threats when that concept is attacked. There are areas such as handling of open-source intelligence (OSINT) that can have an enormous impact on the individual, but where the legal parameters are poorly specified (if they are specified at all). 24 Concerns around the politicization and potential weaponization of personal data also highlight the challenges introduced by having so many perceptions of privacy. 25

Privacy as a Fundamental Human Right

The protection of personal data often refers to autonomy and control over one’s data. This level of autonomy and control varies depending on the context. In general, the definition of privacy differs from country to country or state by state. Even though the US is one of 48 United Nations countries that voted to adopt the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the US does not share the EU’s embrace of privacy as a fundamental human right. For example, instead of a comprehensive, federal law, it is building a patchwork of state-specific laws.

-

In the EU, human dignity is recognized as an absolute fundamental right.

-

In this notion of dignity, privacy, or the right to a private life, to be autonomous, in control of information about yourself, to be let alone, plays a pivotal role. Privacy is not only an individual right but also a social value.

-

The right to privacy or private life is enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Article 12), the European Convention of Human Rights (Article 8), and the European Charter of Fundamental Rights (Article 7). 26

Westin . In the 1960s, Privacy pioneer Alan Westin defined privacy as “The claim of individuals, groups, or institutions to determine for themselves when, how, and to what extent information about them is communicated to others.” 27

US Supreme Court. In 1989, the US Supreme Court wrote, “Both the common law and the literal understandings of privacy encompass the individual’s control of information concerning his or her person.” 28

China . In the People’s Republic of China (PRC), a complex array of laws govern personal data and privacy, due to be eclipsed by comprehensive regulation in the future. The trend indicates “individuals are gaining significant data protection rights in the private sectors but cannot claim any remedies for the infringements of their privacy carried out by the state government.” 29 Today, various laws apply, depending on the sector: financial services, e-commerce, telecommunications, Internet services, content providers, or healthcare.

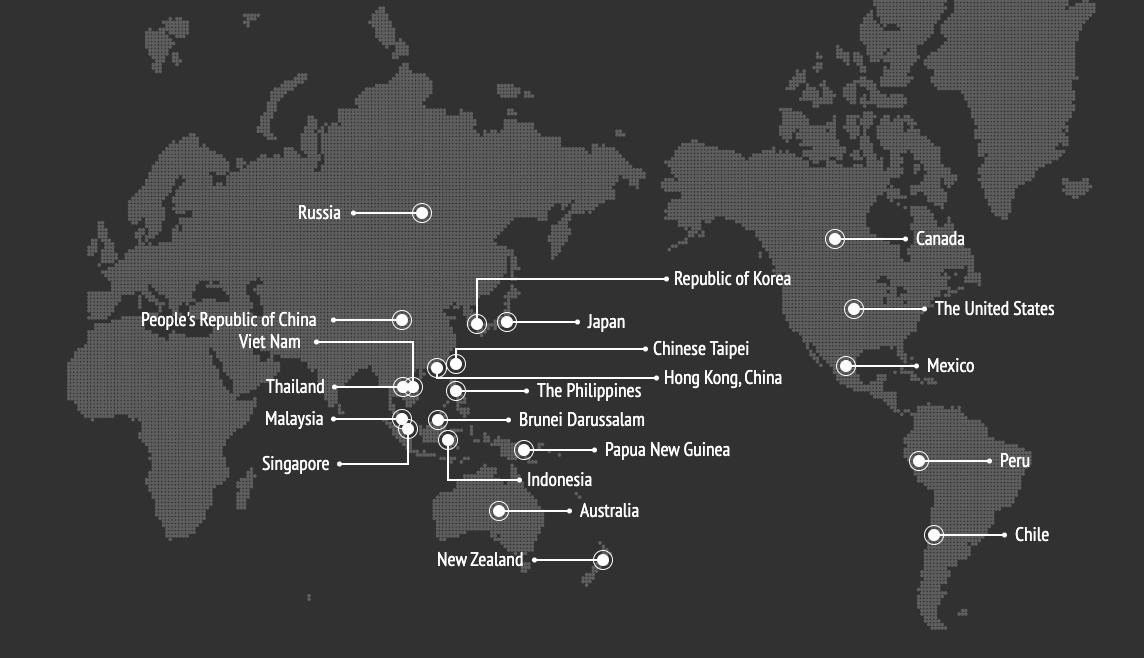

APEC . The Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Privacy Framework can be downloaded here . The APEC Privacy Framework protects privacy within and beyond economies and enables regional transfers of personal information that benefits consumers, businesses, and governments. This framework is used as a basis for the APEC Cross-Border Privacy Rules (CBPR) System. The framework countries and participants include the countries in the map below.

基本的人権としてのプライバシー

多くの場合、個人データの保護は自分のデータに対する自律性と制御を意味します。自律性と制御のレベルは、状況によって異なります。一般に、プライバシーの定義は国ごと、または州ごとに異なります。米国は、世界人権宣言の採択に投票した48の国連加盟国の1つであるにもかかわらず、米国はEUがプライバシーを 基本的人権 として受け入れることを共有していません。たとえば、包括的な連邦法ではなく、州固有の法律のパッチワークで構築しています。

-

EUでは人間の尊厳が絶対的な基本的権利として認められています。

-

尊厳やプライバシー、私生活に対する権利の概念において、自分自身に関する情報を自律的に管理することは、言うまでもなく極めて重要な役割を果たします。プライバシーは個人の権利であるだけでなく、社会的価値でもあります。

-

プライバシーまたは私生活に対する権利は、世界人権宣言(第12条)、欧州人権条約(第8条)、欧州基本権憲章(第7条)に明記されています。 26

Westin . 1960年代、プライバシーの先駆者であるAlan Westinは、プライバシーを「自身に関する情報がいつ、どのように、どの程度の情報が他者に伝達されるかを自ら決定する個人、集団または機関の主張」と定義しました。 27

米国最高裁判所 1989年、米国最高裁判所は、「判例法とプライバシーの文字通りの理解の両方に、個人に関する情報の個人による管理が含まれる」と書いています。 28

中国 . 中華人民共和国(PRC)では、個人データとプライバシーを管理する複雑な法律が制定されており、将来的には包括的な規制によって隠される予定です。この傾向は、「個人は民間部門で重要なデータ保護権を獲得しているが、国家政府によっておこなわれたプライバシーの侵害に対する救済を請求することはできない」ことを示しています。 29 今日、金融サービス、電子商取引、電気通信、インターネットサービス、コンテンツプロバイダーやヘルスケアなど、セクターに応じてさまざまな法律が適用されます。

APEC . アジア太平洋経済協力(APEC)プライバシー・フレームワークは、こちらからダウンロードできます。APECプライバシー・フレームワークは、経済圏内外のプライバシーを保護し、消費者、企業、政府に利益をもたらす個人情報の地域移転を可能にします。このフレームワークは、APEC越境プライバシー規則(CBPR)システムの基礎として使用されています。フレームワークに参加している国と参加者には、下の地図の国が含まれています。

Figure 2 - Map of the APEC Cross-Border Privacy Rules (CBPR) System framework countries and participants 30

Privacy Models

According to Samm Sacks, Senior Fellow Yale Law School, Paul Tsai China Center, there are two basic privacy models: 1) China, and 2) GDPR. She indicates that Viet Nam, Kenya, and India are more closely aligned with China’s model. 31 Even though China’s privacy laws are influenced by the GDPR, they are markedly different both in detail (for example, China supports implied consent, whereas the GDPR requires explicit consent) and in spirit (in general, the rights of the state supersede individual rights). The privacy dichotomy in China is evidenced by the increased protection of consumers from technology companies such as Renren and other Chinese Facebook counterparts, even as government surveillance intensifies.

Beyond privacy law, organizations approach privacy for consumers in a variety of ways. The role of the identity professional is first to understand the organization’s posture with regards to privacy, security, and risk.

プライバシーモデル

Samm Sacks(Senior Fellow Yale Law School, Paul Tsai China Center)によると、基本的なプライバシーモデルは2つあります:1)中国と、2)GDPRです。彼女は、ベトナム、ケニア、インドがより中国のモデルに近いと指摘しています。 31 中国のプライバシー法はGDPRの影響を受けているとはいえ、細部(例えば、中国は暗黙の了解をサポートしているが、GDPRは明示的な了解を要求しています)においても精神(一般に、国家の権利が個人の権利に優先する)においても著しく異なっています。中国のプライバシーの二分は、政府の監視が強化されているにもかかわらず、Renrenや他の中国のFacebookに相当する企業などのテクノロジー企業からの消費者の保護が強化されていることからも明らかです。

プライバシー法を超えて、組織はさまざまな方法で消費者のプライバシーにアプローチします。アイデンティティの専門家の役割は、まずプライバシー、セキュリティ、リスクに関する組織の姿勢を理解することです。

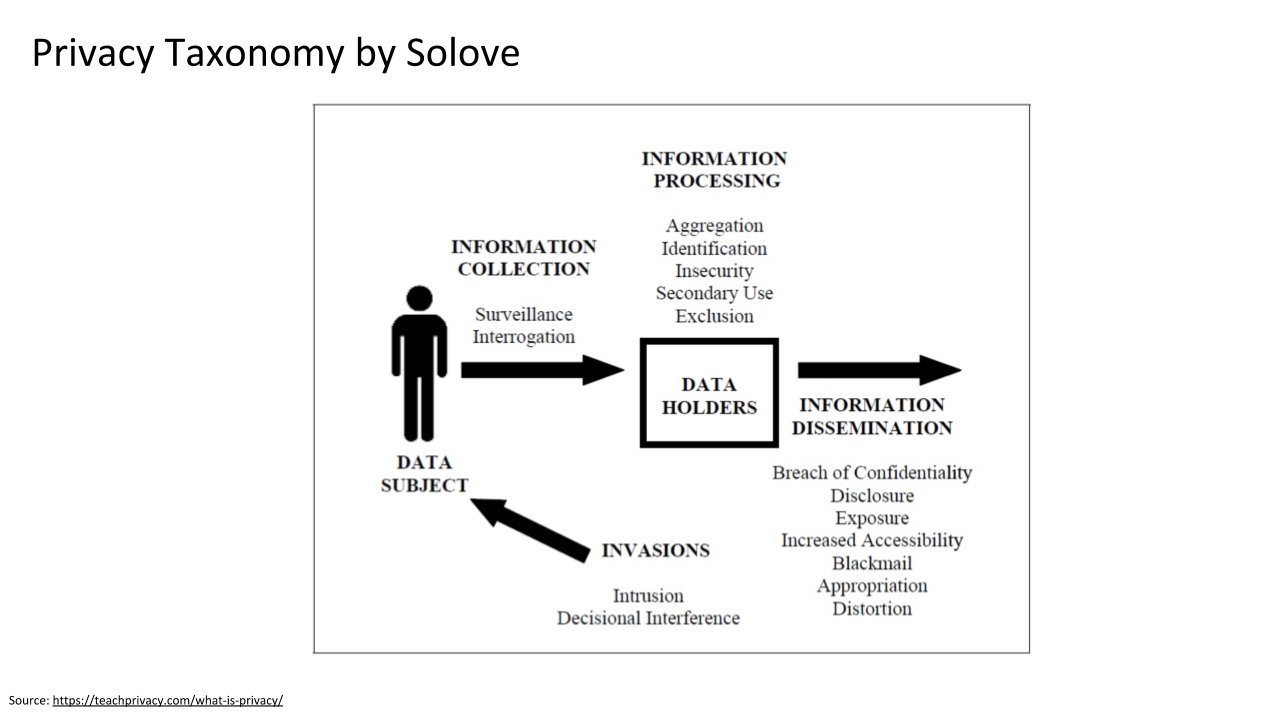

Privacy Taxonomy

One of the world’s leading experts on privacy law is Daniel Solove, the John Marshall Harlan Research Professor of Law at the George Washington University Law School. As depicted in Solove’s privacy taxonomy below, privacy has two main parties:

-

The Data Subject, or consumer

-

The Data Holders, or data processor and controller

The four main processes in the privacy taxonomy comprise:

-

Information Collection

-

Information Processing

-

Information Dissemination

-

Invasions

The four processes may be viewed in order, starting with Information Collection and ending with Invasions. The Information Collection of data about a Data Subject is done by the Data Holder, or data processor and controller to put it in GDPR terms. The collection of data about a Data Subject or individual may be done by another individual, business, government, or external organization via surveillance or interrogation. The Information Processing includes the storage of data and any additional steps taken to apply something like a software algorithm to further derive value. Insecurity refers to a lack of security. Information Dissemination includes many harmful things that might result if the information is part of a list of undesirable actions, including a Breach of Confidentiality, Disclosure, Exposure, Blackmail, or Distortion. Invasions include intrusion and decisional interference, which Solove describes as “the government’s incursion into the data subject’s decisions regarding her private affairs.” 32

プライバシー分類法

プライバシー法の世界的な第一人者は、George Washington University Law SchoolのJohn Marshall Harlan Research Professor of LawであるDaniel Soloveです。Soloveのプライバシー分類法では、以下のようにプライバシーには2つの主体があるとされています:

-

データ対象者か消費者

-

データ保有者かデータ処理者でありデータ管理者

プライバシー分類法における4つの主要なプロセスは、以下のように構成されます:

-

情報収集

-

情報処理

-

情報発信

-

侵害

この4つのプロセスは、情報収集から始まり侵害に終わるという順序で見ることができます。データ対象者に関するデータの情報収集は、データ保有者またはGDPRの用語で言うところのデータ処理者および管理者によっておこなわれます。データ対象者または個人に関するデータの収集は、他の個人、企業、政府または外部組織が監視または尋問によっておこなうことができます。情報処理には、データの保存とさらに価値を引き出すためにソフトウェアアルゴリズムのようなものを適用するために実施される追加の手順が含まれます。インセキュリティーとは、セキュリティーの欠如を指します。情報発信には、機密保持違反、開示、暴露、脅迫、歪曲など、情報が望ましくない行為のリストの一部である場合に生じるかもしれない多くの有害な事柄が含まれます。侵害には、強制と意思決定への干渉があり、Soloveはこれらを「データ対象者の私的な事柄に関する意思決定への政府による強制」と表現しています。 32

Figure 3 - Privacy Taxonomy by Solove

[Permission received from author to use this graphic]

Privacy by Design

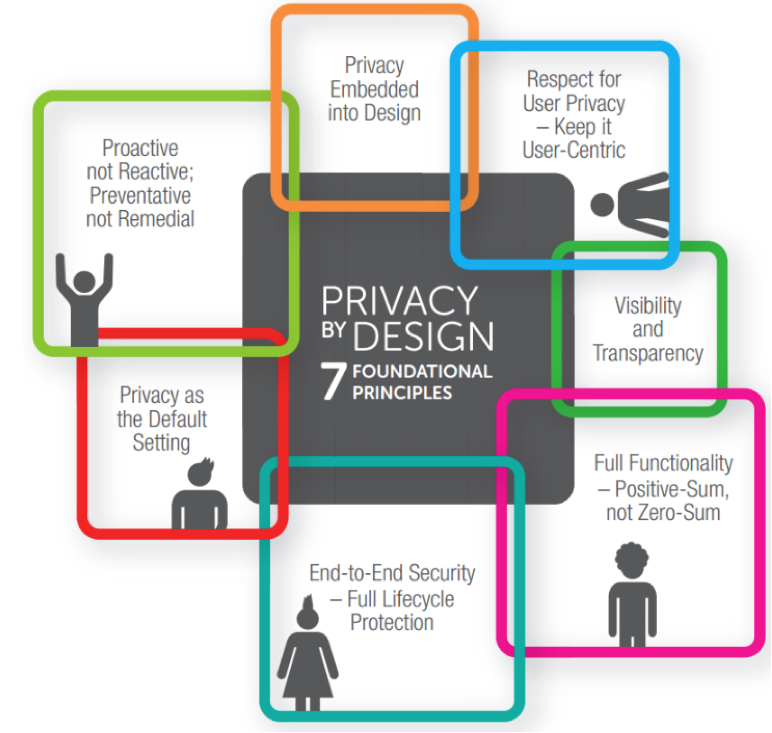

Privacy by Design is the brainchild of Ann Cavoukian, one of the world’s leading privacy experts; former Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario, Canada; former distinguished visiting professor at Ryerson University, where she was also Executive Director of the Ryerson’s Privacy and Big Data Institute; and founder of Global Privacy and Security by Design Centre . Originally published in 2009, the Privacy by Design Principles , depicted in the figure below, are an integral part of the GDPR and subsequent GDPR-influenced privacy laws. Privacy by Design takes a holistic, systems engineering approach and makes it clear that compliance with regulations is not enough. Privacy by Design advances the view that the future of privacy cannot be assured solely by compliance with regulatory frameworks; rather, privacy assurance must ideally become an organization’s default mode of operation. 33

In the Privacy by Design figure below, note that privacy by default is one of the seven principles. The sharp contrast of cultural expectations may come as a surprise to some. As a gross generalization, the EU sensibility is to have privacy by default as the norm, whereas in the US, privacy by default is the rare exception.

プライバシー・バイ・デザイン

プライバシー・バイ・デザインは、世界有数のプライバシー専門家であり、元Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario, Canada、Ryerson Universityの元名誉客員教授で、Executive Director of the Ryerson’s Privacy and Big Data Institute、 Global Privacy and Security by Design Centreの創設者でもあるAnn Cavoukianが発案したものです。2009年に発表されたプライバシー・バイ・デザイン原則は、下図で示すように、GDPRおよび後続のGDPRの影響を受けたプライバシー法の不可欠な要素です。プライバシー・バイ・デザインは、全体論的なシステム工学的アプローチをとり、規制を遵守するだけでは不十分であることを明確に示しています。プライバシー・バイ・デザインは、プライバシーの未来は規制のフレームワークへの準拠だけでは保証されないという見解を示しています;むしろ、プライバシー保証は、理想的には組織のデフォルトの運用モードとならなければなりません。 33

以下のプライバシー・バイ・デザインの図は、 privacy by default は7つの原則のうちの1つであることに注意してください。このような文化的な違いに驚かれる方もいるかもしれません。一般論として、EUの感覚では、デフォルトでプライバシーを確保することが標準であるのに対し、米国では、デフォルトでプライバシーを確保することは稀な例外です。

A universal identity system will have profound impacts on privacy since the digital identities of people - and the devices associated with them - constitute personal information. Great care must be taken that an interoperable identity system does not become an infrastructure of universal surveillance.

全世界的なアイデンティティ・システムはプライバシーに重大な影響を与えるでしょう。なぜなら、人々のデジタル・アイデンティティと人々が持つデバイスが個人情報を構成するからです。相互運用可能なアイデンティティ・システムは全世界的な監視インフラとならないように、細心の注意が払われなければなりません。

Compliance is Necessary but not Sufficient

To a limited extent, privacy law enforces data protection. This section applauds the advances of privacy law, plus it explores some of the failings, flaws, and shortcomings of privacy law, including consent issues, time lag, and reactive posture because the law cannot keep pace with current innovations, and what Harvard’s Shoshana Zuboff calls the asymmetric power stranglehold of Google, Facebook and others that are immune from the effective impact of privacy law because the law does not cover much of what they do with the collection of behavioral surplus.

-

Compliance ≠ Privacy or Security. As an identity professional, remember that just because you are compliant does not mean you have achieved the appropriate level of privacy and security required by your organization (or expected by your customers), hopefully documented in its risk and privacy policies.

-

Privacy Law’ Gap Growth’ is Exponential. Distinguished Fellow at Harvard Law, Vivek Wadha explains, “The gaps in privacy laws have grown exponentially. These regulatory gaps exist because laws have not kept up with advances in technology. The gaps are getting wider as technology advances ever more rapidly.” 36

Privacy and compliance capabilities are foundational for any Consumer Identity & Access Management (CIAM) program because they protect the personal data of consumers as well as safeguard organizations by defining guidelines for compliance in alignment with the organization’s privacy, security, and risk management policies. If organizations do not comply, there are many negative consequences, including:

-

Fines (for GDPR, up to €20 million or 4% of annual turnover, whichever is highest)

-

Reputational or brand damage

-

Loss of customers, loyalty erosion

-

Lawsuits

-

CEO may be held personally responsible

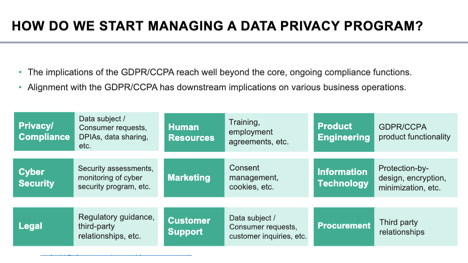

As an identity professional, you may be part of a team responsible for some or all aspects of privacy and compliance for consumers. This section will enable you to contribute and have a basic understanding of jurisdiction, consent, and data protection across the entire organization. For GDPR or CCPA compliance, you may interact with human resources, product engineering, security, marketing, IT, legal, customer support, procurement, and beyond, as shown in the figure below.

準拠は必須だが充分ではない

プライバシー法は限られた範囲内でデータ保護を実施します。このセクションでは、プライバシー法の進歩に拍手を送るとともに、同意の問題、タイムラグ、法律が現在の技術革新に追いつけないために後手に回る姿勢、そして、ハーバード大学のShoshana Zuboffが、GoogleやFacebookなどが行動余剰の収集でおこなうことの多くを法律がカバーしていないためにプライバシー法の有効な影響から免れる非対称権力の束縛と呼ぶものについて、プライバシー法の失敗、欠陥、欠点について探っています。

-

コンプライアンス≠プライバシーまたはセキュリティ アイデンティティの専門家として、コンプライアンス準拠だけでは組織が要求する(または顧客が期待する)適切なレベルのプライバシーおよびセキュリティ(可能であればリスクおよびプライバシーポリシーで文書化)を達成したことにはならないことを忘れないようにすること。

-

プライバシー法のギャップは指数関数的に拡大している ハーバード・ロー・スクールの特別研究員であるVivek Wadhaは、「プライバシー法におけるギャップは指数関数的に拡大しています。このような規制のギャップが存在するのは、法律がテクノロジーの進歩に追いついていないためです。技術の進歩がますます速くなるにつれて、ギャップはますます広がっています。」と説明しています。 36

プライバシーとコンプライアンスの機能は、あらゆるコンシューマー・アイデンティティとアクセス管理(CIAM)プログラムの基礎となるもので、組織のプライバシー、セキュリティおよびリスク管理のポリシーに沿ったコンプライアンスのガイドラインを定義することによって、消費者の個人データを保護し、組織を保護します。組織がコンプライアンスに準拠しない場合、次のような多くの悪影響があります:

-

罰金(GDPRの場合、最大2000万ユーロまたは年間売上高の4%のいずれか高い方)

-

風評被害、ブランド毀損

-

顧客の喪失、ロイヤリティの低下

-

訴訟

-

CEOの個人的な責任が問われる可能性

アイデンティティの専門家として、消費者のプライバシーとコンプライアンスの一部または全側面を担当するチームの一員となることがあります。このセクションでは、組織全体にわたる管轄権、同意およびデータ保護について貢献し、基本的な理解を得ることができます。GDPRまたはCCPAの準拠のために、下図に示すように、人事、製品エンジニアリング、セキュリティ、マーケティング、IT、法務、カスタマーサポート、調達およびそれ以外の担当者とやり取りすることがあります。

Why Consumer Services Need Different Privacy and Compliance Strategies

CIAM and Workforce IAM

Privacy and compliance strategies for workforce IAM have some overlap with CIAM, but CIAM differs in some key regards. For this reason, simply applying workforce privacy and compliance to CIAM projects may not be optimal. Below are some of the key differences between privacy and compliance strategies for workforce versus CIAM projects:

-

SCALE: CIAM scale is often orders of magnitude greater to reflect a large consumer population versus a smaller, more predictable number of employees and workforce

-

CUSTOMER EXPERIENCE (CX): CX requirements for consumers are more demanding. For its members, IAPP provides a GDPR-centric document, The UX Guide for Getting Consent:

-

“Consent is at the very heart of data protection and privacy,” and while it is important, it is not the be-all and end-all of a privacy program. For example, a layered or intelligent privacy notice strategy can help make privacy interactions less cumbersome.

-

The data subject must have a say in how personal data is collected, used, shared, and destroyed.

-

Even if a choice doesn’t appear to be promoted, wording, widget, and sequence matter. 38

-

-

LAW: Depending on the jurisdiction, the privacy law may differ in some cases for IAM versus CIAM.

-

AUTOMATION: Appropriate levels of automation differ to meet spikey or unpredictable consumer demand.

-

ADVERTISING: Online behavioral advertising in particular, and any advertising in general, is typically aimed at consumers, not the workforce.

-

MACHINE LEARNING AND PROFILING: What the GDPR refers to as “automated processing”, including profiling (automated processing of personal data to evaluate certain things about an individual); plus, machine learning is often applied to consumer data for different purposes for the workforce versus consumers.

なぜコンシューマーサービスは異なるプライバシーおよびコンプライアンス戦略を必要とするのか

CIAMと従業員IAM

従業員IAM向けのプライバシーおよびコンプライアンス戦略はCIAMと一部同じですが、いくつかの重要な部分でCIAMと異なります。この理由で、従業員向けのプライバシーおよびコンプライアンスをCIAMプロジェクトに単純に適用することは最適ではないでしょう。従業員向けのプライバシーおよびコンプライアンス戦略とCIAMプロジェクトの重要な違いは、以下になります:

-

規模:CIAMの規模はしばしば大規模な消費者を反映するために桁違いに大きくなるのに対し、従業員および労働者の数は少なく、予測可能です。

-

カスタマーエクスペリエンス(CX):消費者向けのCX要件はより厳しいです。IAPPはGDPRを主眼にした資料 The UX Guide for Getting Consent を提供しています:

-

「同意はデータ保護およびプライバシーのまさに中心」 であり、重要ですが、プライバシープログラムの全てではありません。例えば、階層化されたまたはインテリジェント・プライバシー通知戦略は、プライバシーのやり取りが煩雑にならないようにします。

-

データ主体は個人データがどのように収集、利用、共有、破棄されるのかについて発言権を持たなければなりません。

-

選択肢が推奨されたり、表示されたり、ウィジェットされたり、羅列されなかったとしてもです。 38

-

-

法律:管轄によっては、いくつかのケースではIAMとCIAMでプライバシー法が異なるかもしれません。

-

自動化:自動化の適切なレベルは、急激または予測不可能な消費者の要求によって異なります。

-

広告:特にオンライン行動広告および一般的な広告は、概して労働者ではなく消費者をターゲットにしています。

-

機械学習とプロファイリング:GDPRで「自動処理」と呼ばれている、プロファイリング(個人に関する特定の事柄を評価するために個人データを自動処理すること)を含みます;加えて、しばしば機械学習には労働者と消費者で異なる目的のために消費者データが適用されます。

CIAM and Social Identity

CIAM often relies on integration with social media identity providers. There are several benefits to this direction, including reducing end-user friction during sign-up and self-service registration, generating fewer usernames and passwords for the end-user to memorize, and simplified business processes that allow for outsourcing user account recovery processes. This integration is not without drawbacks, however, as integration with social media identity providers may enable cross-site tracking of users without their permission.

CIAMとソーシャルアイデンティティ

CIAMは多くの場合ソーシャルメディア・アイデンティティ・プロバイダーとの連携に依存しています。この方向性には、サインアップとセルフサービス登録でのエンドユーザーの摩擦の低減、エンドユーザが記憶するユーザー名とパスワードの削減、アカウント回復プロセスの外部化を可能とするシンプルなビジネスプロセスなどのいくつかのメリットがあります。しかし、この連携に欠点がないわけではなく、ソーシャルメディア・アイデンティティ・プロバイダーとの連携は、ユーザーのクロスサイトトラッキングを許可なく可能にするかもしれません。

Security is Critical

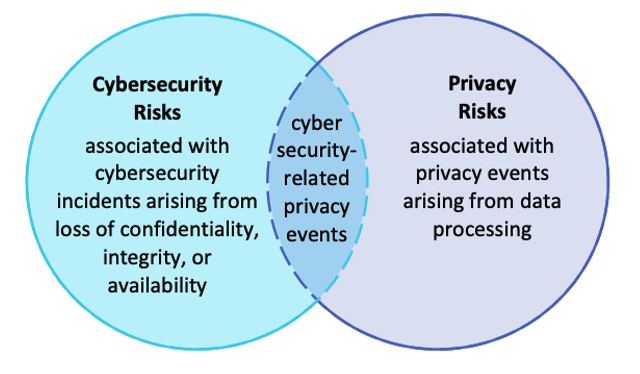

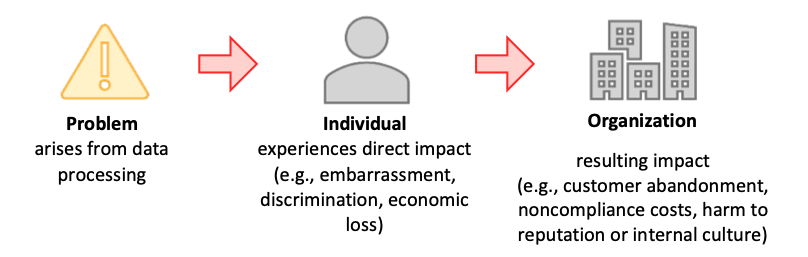

Identity professionals need to understand their organization’s risk management policies for security and privacy and work in concert with their colleagues who create those policies, as well as those responsible for the implementation of the policies. The security policy is a necessary dependency for any successful privacy policy. There is a saying, “You can have security without privacy, but you can’t have privacy without security.” 39 Security or cybersecurity may be used interchangeably. Some also use the term information security. In the figure below from the NIST Privacy Framework, the relationship between cybersecurity risks and privacy risks makes it clear that managing cybersecurity risk may help mitigate privacy risk, but it is not sufficient because privacy risk can result from incidents outside the realm of cybersecurity incidents. For example, smart meters or smart thermostats may collect and record personal data and possibly represent a privacy risk even though they are operating as intended.

Security is Critical

アイデンティティの専門家はセキュリティとプライバシーに関する組織のリスク管理ポリシーを理解する必要があり、それらのポリシーを作成したりポリシーを実装する責任をもっていたりする同僚と協力して作業する必要があります。セキュリティポリシーは、プライバシーポリシーを成功させるために必要な依存関係です。「プライバシーなしのセキュリティを確保できるが、セキュリティなしにプライバシーを確保できない」と言われています。 39 セキュリティまたはサイバーセキュリティは同じ意味で使われることがあります。また、情報セキュリティという用語を使うひともいます。NIST Privacy Frameworkから引用した以下の図は、サイバーセキュリティリスクとプライバシーリスクの関係からサイバーセキュリティリスクを管理することがプライバシーリスクの対策になる一方で、サイバーセキュリティインシデントの範囲外のインシデントからプライバシーリスクが生じる可能性があることから充分ではないことを明らかにしています。例えば、スマートメーターやスマートサーモスタットは個人データの収集と記録をおこなう可能性があり、意図したとおりに動作していてもプライバシーリスクとなる可能性があります。

Privacy Policy is a Business Decision

An in-depth understanding of an organization’s policies will provide clarity for the identity professional’s role in privacy and compliance for consumers. For example, in some cases the marketing department may need to collect extensive personal data, and the organization’s privacy policy may allow this. In other cases, the organization’s business may depend on trust and confidentiality of personal data; and there may be ample budget to ensure data protection for consumers in a visible, transparent, and robust manner.

プライバシーポリシーはビジネス上の決定である

組織のポリシーを深く理解することで、消費者のプライバシーとコンプライアンスにおけるアイデンティティ専門家の役割が明確になります。たとえば、場合によっては、マーケティング部門が広範な個人データを収集する必要があり、組織のプライバシーポリシーでこれが許可されることがあります。また、組織のビジネスが個人データの信頼性と機密性に依存している場合もあります;また、消費者のデータ保護を目に見え、投影性があり、堅牢な方法で確実におこなうための十分な予算があるかもしれません。

-

Mitigate . Mitigating the risk (e.g., organizations may be able to apply technical and/or policy measures to the systems, products, or services that minimize the risk to an acceptable degree);

-

Transfer . Transferring or sharing the risk (e.g., contracts are a means of sharing or transferring risk to other organizations, privacy notices, and consent mechanisms are a means of sharing risk with individuals);

-

Avoid . Avoiding the risk (e.g., organizations may determine that the risks outweigh the benefits, and forego or terminate the data processing); or

-

Accept . Accepting the risk (e.g., organizations may determine that problems for consumers are minimal or unlikely to occur; therefore, the benefits outweigh the risks, and it is not necessary to invest resources in mitigation). 42

-

軽減 . リスクの軽減(例えば、組織はリスクを許容できる程度に最小化するシステム、製品、またはサービスに技術的および/またはポリシー的手段を適用できる場合があります);

-

転嫁 . リスクの転嫁または共有(例えば、契約はリスクを他の組織に共有または転嫁する手段であり、プライバシー通知と同意メカニズムはリスクを個人と共有する手段です);

-

回避 . リスクの回避(例えば、組織はリスクが利益を上回ると判断し、データ処理を中止または終了する場合があります);または

-

受容 . リスクの受容(例えば、組織は消費者にとっての問題が最小限である、または発生する可能性が低いと判断する場合があります;そのため、メリットがリスクを上回り、緩和にリソースを投資する必要はありません) 42

Is Privacy a Competitive Advantage?

As noted above, laws and regulations typically lag innovative product and service offerings. Compliance with current and upcoming privacy laws is only the start. Privacy may be a competitive advantage or not. It depends on your organization and its consumers. In 2010, data protection pioneer and expert Alan Westin was paraphrased, “The idea that privacy can be used as a business advantage is dead, privacy controls are too complex for consumers to understand and a certification culture would be more effective.” 43 Others take the counterargument. Organizations realize that many consumers would enjoy greater control over their data. Privacy for consumers is an opportunity to build trust. Among others, a GDPR and CCPA paper from Akamai provides “tips to build customer trust through regulatory compliance and identity governance.” 44

プライバシーは競争優位となるか?

上述のように、一般的に法律や規制は、革新的な製品やサービスの提供に遅れをとります。現在および将来の個人情報保護法への準拠は、スタート地点に過ぎません。プライバシーが競争上の優位性を持つかどうかは、組織と消費者次第です。2010年、データ保護のパイオニアであり専門家であるAlan Westinは、「プライバシーをビジネスの優位性に利用できるという考えは死に、プライバシー管理は消費者には複雑すぎて理解できないし、認定文化の方がより効果的だ」と表現しました。 43 また、反論をする人もいます。組織は、多くの消費者が自分のデータをよりよく管理できることを喜ぶと認識しています。消費者にとってのプライバシーは、信頼を構築する機会です。AkamaiのGDPRおよびCCPAに関する論文では、「規制遵守とアイデンティティガバナンスを通じて顧客の信頼を築くためのヒント」が紹介されています。 44

Beyond GDPR: ePrivacy and the New European Strategy for Data

In February 2020, the EU published “A European Strategy for Data.” The continuous advancement and proven EU leadership in data protection is a driving force for the rest of the world.

The European Strategy for Data is sector-specific, e.g., healthcare, and provides for:

-

Data can flow within the EU and across sectors.

-

European rules and values, in particular personal data protection, consumer protection legislation, and competition law, are fully respected.

-

The rules for access to and use of data are fair, practical, and clear, and there are clear and trustworthy data governance mechanisms in place; there is an open but assertive approach to international data flows based on European values. 45

Through its focus on data sovereignty and supporting the privacy of people in its constituency, the European Union provides model guidance on newer technologies such as Decentralized Identity (DID) and Verifiable Credentials. Captured in large part in the Regulation on electronic identification and trust services (eIDAS Regulation), this regulation:

-

ensures that people and businesses can use their own national electronic identification schemes (eIDs) to access public services available online in other EU countries;

-

creates a European internal market for trust services by ensuring that they will work across borders and have the same legal status as their traditional paper-based equivalents. 46

The eIDAS Regulation is under consideration for an amendment that will further evolve the guidance available to include more information on digital wallets and their use. 47

Blockchain. The European Strategy for Data includes the evaluation of blockchain technology.

- New decentralised digital technologies such as blockchain offer a further possibility for both individuals and companies to manage data flows and usage, based on individual free choice and self-determination. Such technologies will make dynamic data portability in real-time possible for individuals and companies, along with various compensation models. 48

In addition, the French data protection authority, known as the National Commission on Informatics and Liberty (CNIL) , has spearheaded work on “responsible use of the blockchain in the context of personal data” plus the potential privacy risks inherent in the technology.

The challenges raised by blockchains in terms of compliance with human rights and fundamental freedoms necessarily call for a response at the European level. The CNIL is one of the first authorities to officially address the matter and will work cooperatively with its European counterparts to suggest a strong and harmonised approach. 49

GDPRを超えて:ePrivacyとデータに関する欧州の新戦略

2020年2月、EUは「A European Strategy for Data」を発表しました。データ保護におけるEUの継続的な進歩と実績あるリーダーシップは、他の国々への推進力となっています。

データに対する欧州の戦略は、ヘルスケアなど分野別に規定されています:

-

データはEU域内、セクターを超えて流通できる。

-

欧州のルールおよび価値観、特に個人データ保護、消費者保護法および競争法について充分に尊重されている。

-

データへのアクセスや利用に関するルールが公正、実用的かつ明確であり、明確で信頼できるデータガバナンスの仕組みがある;欧州の価値観に基づき、国際的なデータフローに対してオープンでありながら積極的なアプローチをとる。 45

欧州連合はデータ主権に重点を置き、その構成員である人々のプライバシーを支援することを通して、分散型アイデンティティ(DID)や検証可能なクレデンシャルなどの新しい技術に関するモデルガイダンスを提供しています。この規則の大部分は、電子アイデンティティおよびトラストサービスに関する規則(eIDAS規則)に盛り込まれています:

-

国民や企業が自国の電子アイデンティティスキーム(electronic identification schemes、eIDs)を使って、他のEU諸国のオンライン公共サービスを利用できるようにする;

-

トラストサービスが国境を越えて機能し、従来の紙ベースの同等サービスと同じ法的地位を有することを保証するで、トラストサービスの欧州域内市場を作り出す。 46

eIDAS規則は、デジタルウォレットとその使用に関するより多くの情報を盛り込むため、利用可能なガイダンスをさらに進化させる改正が検討されています。 47

ブロックチェーン 欧州のデータ戦略には ブロックチェーン技術の評価も含まれています。

- ブロックチェーンなどの新しい分散型デジタル技術は、個人と企業の双方が、個人の自由な選択と自己決定に基づいて、データの流れと利用を管理できるさらなる可能性を提供します。このような技術は、個人と企業にとって、リアルタイムでのダイナミックなデータポータビリティを可能にし、様々な補償モデルも可能にします。 48

さらに、フランスのデータ保護当局であるNational Commission on Informatics and Liberty (CNIL)は、「個人データの文脈におけるブロックチェーンの責任ある使用」に加えて、この技術に内在する潜在的なプライバシーリスクに関する作業を率先しておこなっています。

人権と基本的自由の遵守という観点からブロックチェーンが提起する課題は、必然的に欧州レベルでの対応を必要とします。CNILは、この問題に公式に対処する最初の当局の1つであり、 欧州のカウンターパートと協力して、強力で調和のとれたアプローチを提案する予定です。 49

Conclusion

Although it may be difficult to define privacy, the fundamental principles of Privacy by Design, depicted in Figure 5 above, create a well-defined foundation for understanding and implementing Privacy and Compliance for Consumers . This is why Privacy by Design is included in the GDPR and CCPA, and has significantly influenced subsequent privacy regulations and laws. By now, identity professionals have a clear picture of the interlinked dependencies between identity, privacy, and security. Security protects the data; how privacy is provided is based on business and risk policies. The silver lining for the daunting task of implementing privacy and compliance for consumers is that it may be viewed as a competitive advantage and well worth the extra effort.

結論

プライバシーを定義することは難しいかもしれませんが、上記の図5に描かれているプライバシー・バイ・デザインの基本原則は、 消費者のためのプライバシーとコンプライアンス を理解し、実現するための明確な基盤を作り出します。これが、プライバシー・バイ・デザインがGDPRとCCPAに含まれ、その後のプライバシー規制と法律に大きな影響を与えた理由です。ここまでで、アイデンティティの専門家は、アイデンティティ、プライバシーおよびセキュリティの間の相互にリンクした依存関係を明確に把握しています。セキュリティはデータを保護します;プライバシーをどのように提供するかは、ビジネスとリスクのポリシーに基づきます。消費者のためにプライバシーとコンプライアンスを実装するという困難な作業に対する明るい兆しは、それが競争上の優位性であり、余分な努力を実施するのに充分に値すると見なされる可能性があるということです。

Author Bio

Clare Nelson, CISSP, CIPP/E, AWS Certified Cloud Practitioner; is the CEO of ClearMark Consulting, specializing in business development and product strategy. Prior to that, she was VP Technology Alliances & Channel Sales for Identity Governance and Cloud Privileged Access Management leader Saviynt, responsible for AWS and Google Cloud partnerships. Clare’s passion for cybersecurity includes her specializations in identity and privacy comprising: MFA, IGA, PAM, identity proofing, privacy-preserving authentication based on ZKP, identity theft, AML/KYC, and GDPR. Clare has held leadership positions at Novell, EMC2, Dell, and AllClear ID. She is a co-founder of C1ph3r_Qu33ns, an organization dedicated to cultivating and supporting the careers of women in cybersecurity. Clare is a second-generation yogi and technologist and has a degree in mathematics from Tufts University.

Clare Nelson, CISSP, CIPP/E, AWS Certified Cloud Practitioner; is the CEO of ClearMark Consulting, specializing in business development and product strategy. Prior to that, she was VP Technology Alliances & Channel Sales for Identity Governance and Cloud Privileged Access Management leader Saviynt, responsible for AWS and Google Cloud partnerships. Clare’s passion for cybersecurity includes her specializations in identity and privacy comprising: MFA, IGA, PAM, identity proofing, privacy-preserving authentication based on ZKP, identity theft, AML/KYC, and GDPR. Clare has held leadership positions at Novell, EMC2, Dell, and AllClear ID. She is a co-founder of C1ph3r_Qu33ns, an organization dedicated to cultivating and supporting the careers of women in cybersecurity. Clare is a second-generation yogi and technologist and has a degree in mathematics from Tufts University.

Change Log

| Date | Change |

|---|---|

| 2020-06-17 | V1 published |

| 2021-09-30 | V2 published: Updated date of NY SHIELD act; added section on CIAM and Social Identity; added section title for CIAM and Workforce IAM; added Heather Flanagan as editor |

| 2022-12-18 | V3 published: Updated abstract; added notes re: threats to privacy in “What is Privacy?”; added information on eIDAS in “Beyond GDPR” |

-

“IDPro Body of Knowledge,” IDPro, https://www.idpro.org/body-of-knowledge/ . ↩ ↩2

-

Cormack, Andrew, “Introduction to the GDPR (v2),” IDPro Body of Knowledge, 30 June 2021, https://bok.idpro.org/article/id/11/ . ↩ ↩2

-

Hindle, Andrew, “Impact of GDPR on Identity and Access Management,” IDPro Body of Knowledge, 31 March 2020, https://bok.idpro.org/article/id/24/ . ↩ ↩2

-

“Terminology in the IDPro Body of Knowledge,” IDPro Body of Knowledge, 30 September 2021, https://bok.idpro.org/article/id/41/ . ↩ ↩2

-

Solove, D., “The Myth of the Privacy Paradox,” SSRN e-Library, 24 February 2020, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3536265 . ↩ ↩2

-

Narayanan, Arvind, and Vitaly Shmatikov, “Robust De-anonymization of Large Sparse Datasets,” The University of Texas at Austin, n.d., https://www.cs.utexas.edu/~shmat/shmat_oak08netflix.pdf . ↩ ↩2

-

Narayanan, Arvind, Joanna Huey, and Edward W. Felton, “A Precautionary Approach to Big Data Privacy,” 19 March 2015, https://www.cs.princeton.edu/~arvindn/publications/precautionary.pdf . ↩ ↩2

-

“’Anonymized’ Data Can Never Be Totally Anonymous, says Study,” The Guardian, 24 July 2019, https://cacm.acm.org/news/238352-anonymized-data-can-never-be-totally-anonymous-says-study/fulltext . ↩ ↩2

-

“Complete guide to GDPR compliance,” Horizon 2020 Framework Programme of the European Union, https://gdpr.eu/ . ↩ ↩2

-

“California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA),” Office of the Attorney General, California Department of Justice, https://oag.ca.gov/privacy/ccpa . ↩ ↩2

-

“An act to amend the general business law and the state technology law, in relation to notification of a security breach,” Senate Bill S5575B, The New York State Senate, 7 May 2019, https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2019/s5575 . ↩ ↩2

-

“The California Consumer Privacy Act of 2018,” Assembly Bill No. 375, Chapter 55, California State Legislature, 29 June 2018, https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=201720180AB375 . ↩ ↩2

-

“Data Protection Laws of the World,” map, DLA Piper Intelligence, https://www.dlapiperdataprotection.com/ ↩

-

“Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union,” Official Journal of the European Union, C 392/391, 26 October 2012, http://data.europa.eu/eli/treaty/char_2012/oj . ↩ ↩2

-

“Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union,” Official Journal of the European Union, C 326, 26 October 2012, ttp://data.europa.eu/eli/treaty/tfeu_2012/oj . ↩ ↩2

-

United Nations, “The Universal Declaration of Human Rights,” 1948, https://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/ . ↩ ↩2

-

“APEC Privacy Framework,” International Association of Privacy Professionals (IAPP), n.d., https://iapp.org/resources/article/apec-privacy-framework/ . ↩ ↩2

-

“The new EU ePrivacy Regulation: what you need to know,” i-SCOOP, n.d., https://www.i-scoop.eu/gdpr/eu-eprivacy-regulation/ . ↩ ↩2

-

“Richards, Neil, and Woodrow Hartzog, “The Pathologies of Digital Consent,” SSRN e-Library, 11 November 2019, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3370433 . ↩ ↩2

-

Naughton, John, “’The goal is to automate us’: welcome to the age of surveillance capitalism,” The Guardian, 20 January 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2019/jan/20/shoshana-zuboff-age-of-surveillance-capitalism-google-facebook . ↩ ↩2

-

Petters, Jeff, “Data Privacy Guide: Definitions, Explanations and Legislations,” Varonis, 29 March 2020, https://www.varonis.com/blog/data-privacy/ . ↩ ↩2

-

Maler, Eve, “Don’t Pave Privacy Cow Paths: Retool Consent for the New Mobility” (video), Identiverse 2018, 26 June 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eP5U2sA6EFk&t=254s . ↩ ↩2

-

Hulsen, L. Ten, “Open Sourcing Evidence from the Internet - The Protection of Privacy in Cvilian Criminal Investigations using OSINT (Open-Source Intelligence)”, Amsterdam Law Forum, vol 12.2, 2020, https://heinonline.org/hol-cgi-bin/get_pdf.cgi?handle=hein.journals/amslawf12§ion=9 . ↩ ↩2

-

See for example Clausen, M.-L., 2021. Challenges of using biometrics in Yemen, DIIS: Dansk Institut for Internationale Studier. Retrieved from https://policycommons.net/artifacts/1526658/challenges-of-using-biometrics-in-yemen/2214896/ on 10 Nov 2022. CID: 20.500.12592/n9640f. ↩ ↩2

-

“Data Protection,” European Data Protection Supervisor, n.d., https://edps.europa.eu/data-protection/data-protection_en ↩ ↩2

-

Westin, Alan F. “Privacy and freedom.” Washington and Lee Law Review 25, no. 1 (1968): 166. ↩ ↩2

-

Cate, Fred H., Beth E. Cate, “The Supreme Court and information privacy,” International Data Privacy Law, Volume 2, Issue 4, November 2012, p 255-267, https://doi.org/10.1093/idpl/ips024 . ↩ ↩2

-

Pernot-Leplay, Emmanuel, “Data Privacy Law in China: Comparison with the EU and U.S. Approaches,” (blog post), 27 March 2020, https://epernot.com/data-privacy-law-china-comparison-europe-usa/ . ↩ ↩2

-

Member Economies map, Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, https://www.apec.org/About-Us/About-APEC/Member-Economies . ↩

-

Sacks, Samm. “China’s Emerging Data Privacy System and GDPR.” Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies (2018). ↩ ↩2

-

Solove, Daniel J, “A Taxonomy of Privacy,” University of Pennsylvania Law Review, Vol. 154, No. 3, January 2006, https://www.law.upenn.edu/journals/lawreview/articles/volume154/issue3/Solove154U.Pa.L.Rev.477(2006).pdf . ↩ ↩2

-

Cavoukian, Ann, “Privacy by Design: The 7 Foundational Principles,” www.privacybydesign.ca , n.d., https://www.ipc.on.ca/wp-content/uploads/Resources/7foundationalprinciples.pdf . ↩ ↩2

-

“Privacy By Design,” graphic, Aristi Ninja, n.d., https://aristininja.com/privacy-by-design/ . ↩

-

Cavoukian, Ann, “7 Laws of Identity: The Case for Privacy-Embedded Laws of Identity in the Digital Age,” Information and Privacy Commission of Ontario, n.d., https://collections.ola.org/mon/15000/267376.pdf . ↩ ↩2

-

Wadhwa, Vivek, “Laws and Ethics Can’t Keep Pace with Technology,” MIT Technology Review, 15 April 2014, https://www.technologyreview.com/s/526401/laws-and-ethics-cant-keep-pace-with-technology/ . ↩ ↩2

-

ISACA webinar, Robotic Process Automation (RPA) and Audit, March 19, 2020, https://www.isaca.org/education/online-events/lms_w031920 ↩

-

“The UX Guide for Getting Consent,” IAPP, n.d., https://iapp.org/store/books/a191a000002FUZKAA4/ . ↩ ↩2

-

Schwartz, Karen D., “Data Privacy and Data Security: What’s the Difference?” ITPro Today, 2 May 2019, https://www.itprotoday.com/security/data-privacy-and-data-security-what-s-difference . ↩ ↩2

-

“NIST Privacy Framework: A Tool for Improving Privacy Through Enterprise Risk Management, Version 1.0,” National Institute of Standards and Technology, U.S. Department of Commerce, 16 January 2020, https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/CSWP/NIST.CSWP.01162020.pdf . ↩

-

Ibid ↩

-

“NIST Privacy Framework: A Tool For Improving Privacy Through Enterprise Risk Management,” Preliminary Draft, National Institute of Standards and Technology, U.S. Department of Commerce, 6 September 2019, https://www.nist.gov/system/files/documents/2019/09/09/nist_privacy_framework_preliminary_draft.pdf . ↩ ↩2

-

“The Privacy Advisor,” IAPP, Vol. 10, No. 10, December 2010, https://iapp.org/media/pdf/publications/Advisor_12-10_print.pdf . ↩ ↩2

-

“White Paper: GDPR, CCPA, and Beyond: How to Comply with Data Privacy Laws and Improve Customer Trust,” Akamai, n.d., https://www.akamai.com/us/en/campaign/assets/whitepapers/gdpr-ccpa-and-beyond-wp.jsp . ↩ ↩2

-

“Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions,” European Commission, COM(2020) 66 final, 19 February 2020

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0066&from=EN . ↩ ↩2

-

European Commission, “eIDAS Regulation,” website, last updated 7 June 2022, https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/eidas-regulation . ↩ ↩2

-

European Commission, “Commission proposes a trusted and secure Digital Identity for all Europeans,” press release, 3 June 2021, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_21_2663 . ↩ ↩2

-

European Commission, COM(2020) 66 final, 19 February 2020. ↩ ↩2

-

“Blockchain and the GDPR: Solutions for a responsible use of the blockchain in the context of personal data,” CNIL, 6 November 2018,

https://www.cnil.fr/en/blockchain-and-gdpr-solutions-responsible-use-blockchain-context-personal-data . ↩ ↩2